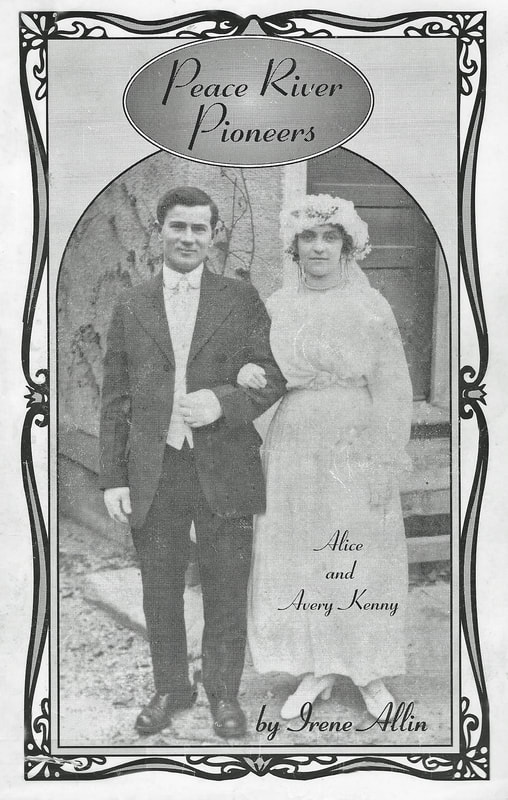

Peace River Pioneers

The Peace River Pioneers is a book/story written by Avery Arthur Kenny's daughter Agnes Irene Allin (Kenny) and published circa 1990. A number of copies of this have been circulated amongst the family descendants.

This webpage attempts to make the story available to all who are interested, and Irene stated it was a true story. We should note that;

a) Irene was in her 70s when she wrote this book, and some of her memories may not match the memories of her siblings.

b) Descriptions of some events might seem fantastical in today's society, but strange events did often occur in pioneer days.

Peace River Pioneers has been formatted and published by webmaster Keith Millard (a Kenny Cousin) in association with Marion Chell (Irene's daughter and Avery's granddaughter) and by Karen Wemyss (Arthur Roy Kenny's daughter and Avery's granddaughter). We have also been assisted by Marj Kenny and her mother Alice Kenny (Avery's daughter-in-law).

Index:

a) - Introduction

b) - The Beginning - Part 1

c) - The Beginning - Cont'd

d) - The Edson Trail - Part 1

e) - The Edson Trail - Cont'd

f) - The Homestead

g) - The Annual Sports Day

h) - Trials and Rewards

i) - Honeymoon Trip North

j) - Alice Takes up the Task

k) - The Family Begins

l) - Carmie's Story

m) - Enter: The Fur Industry

n) - Goodbye to Farm and Friends

o) - Life at Faust

p) - Footnote Regarding Grande Prairie & Edson Trail History

q) - Family Galleries

Note: A separate webpage has been set up to contain the published childhood memories of Irene Kenny. To visit that page, click on

Irene's Childhood Memories.

This webpage attempts to make the story available to all who are interested, and Irene stated it was a true story. We should note that;

a) Irene was in her 70s when she wrote this book, and some of her memories may not match the memories of her siblings.

b) Descriptions of some events might seem fantastical in today's society, but strange events did often occur in pioneer days.

Peace River Pioneers has been formatted and published by webmaster Keith Millard (a Kenny Cousin) in association with Marion Chell (Irene's daughter and Avery's granddaughter) and by Karen Wemyss (Arthur Roy Kenny's daughter and Avery's granddaughter). We have also been assisted by Marj Kenny and her mother Alice Kenny (Avery's daughter-in-law).

Index:

a) - Introduction

b) - The Beginning - Part 1

c) - The Beginning - Cont'd

d) - The Edson Trail - Part 1

e) - The Edson Trail - Cont'd

f) - The Homestead

g) - The Annual Sports Day

h) - Trials and Rewards

i) - Honeymoon Trip North

j) - Alice Takes up the Task

k) - The Family Begins

l) - Carmie's Story

m) - Enter: The Fur Industry

n) - Goodbye to Farm and Friends

o) - Life at Faust

p) - Footnote Regarding Grande Prairie & Edson Trail History

q) - Family Galleries

Note: A separate webpage has been set up to contain the published childhood memories of Irene Kenny. To visit that page, click on

Irene's Childhood Memories.

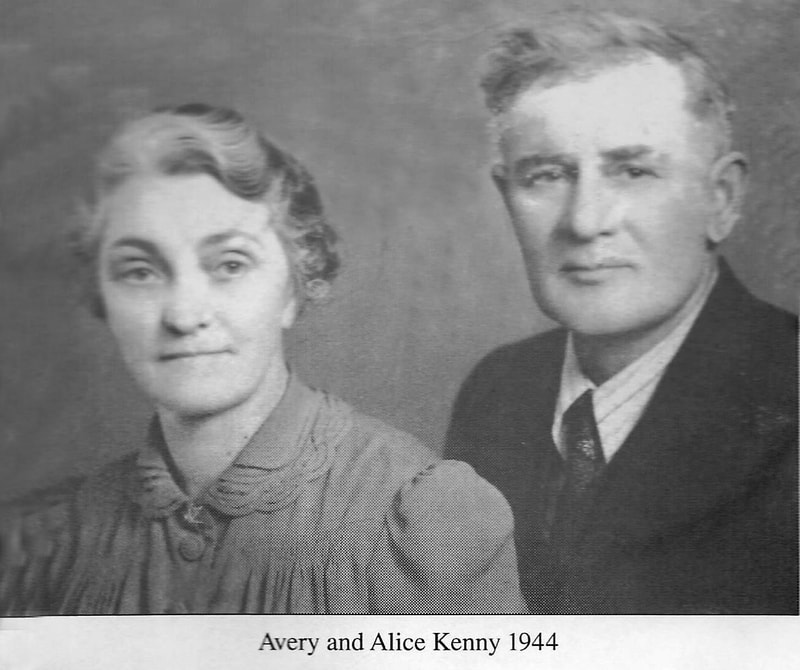

a) - Introduction: Editors Note

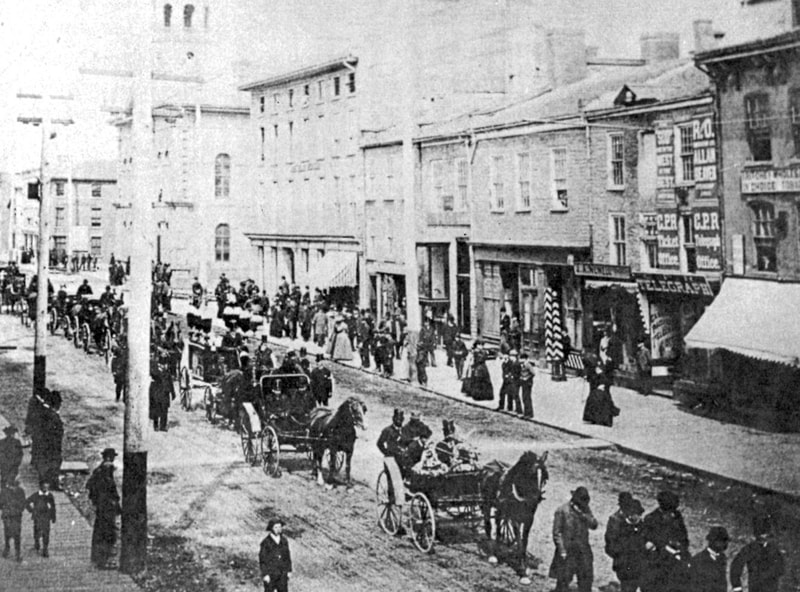

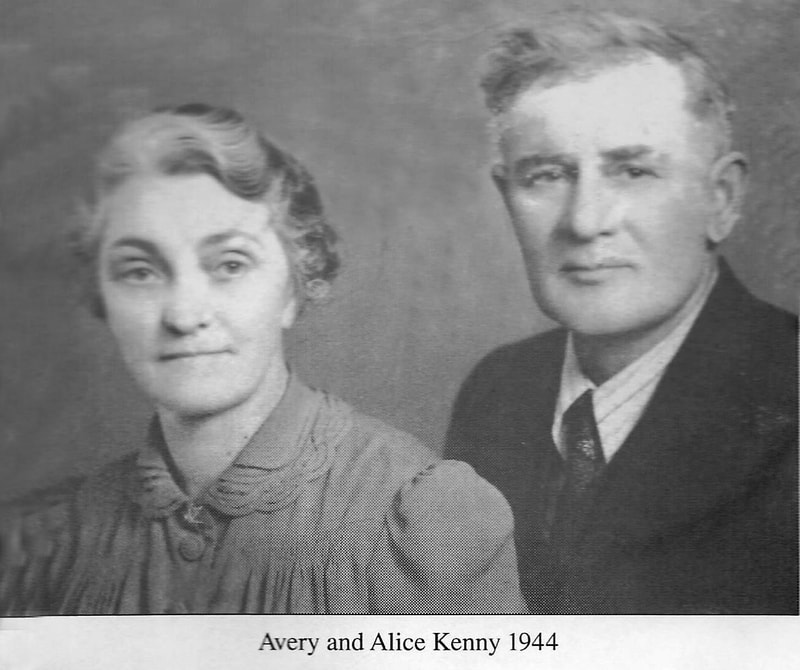

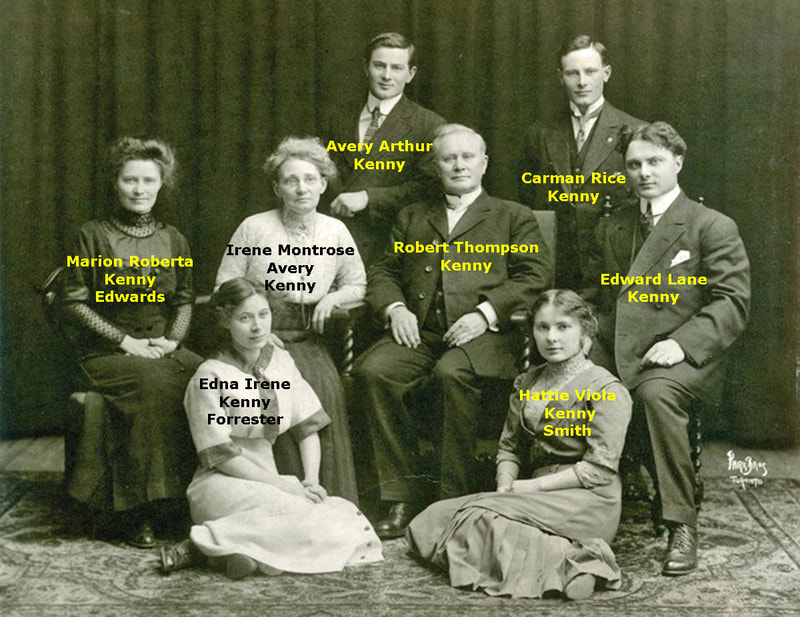

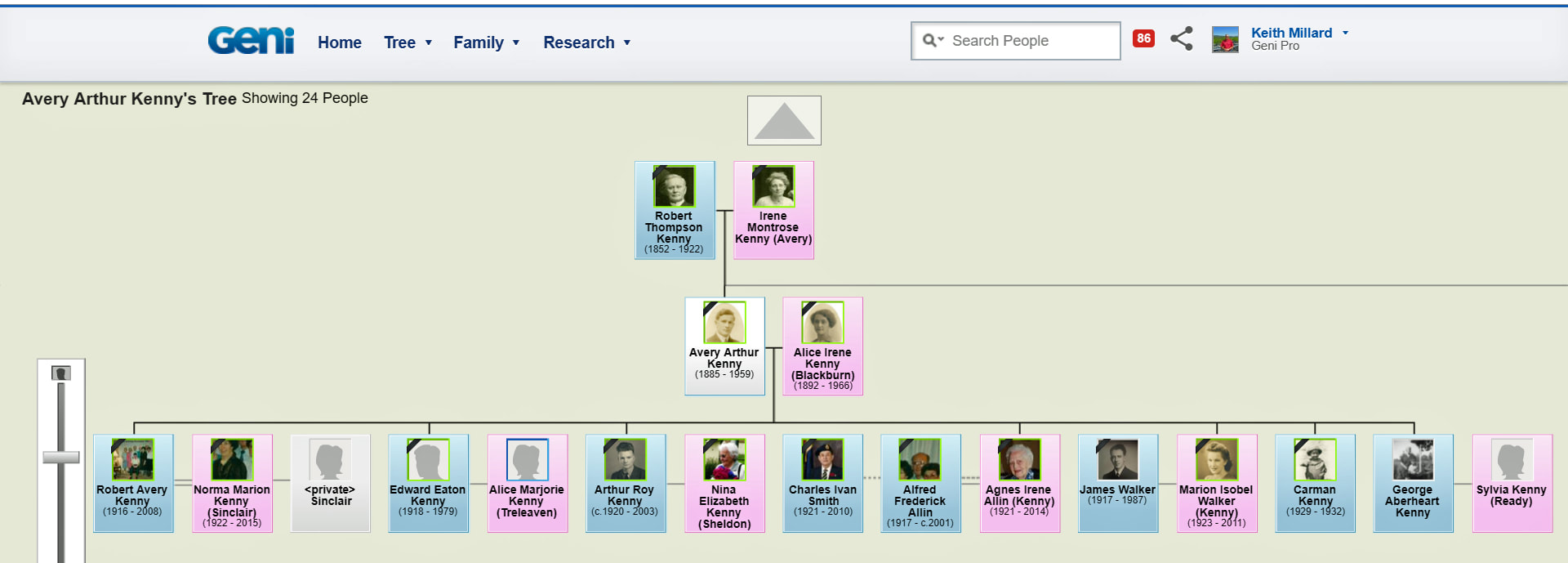

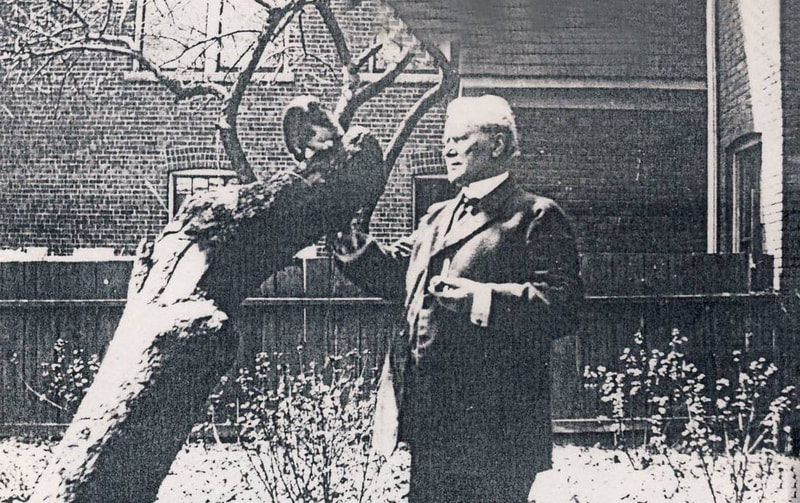

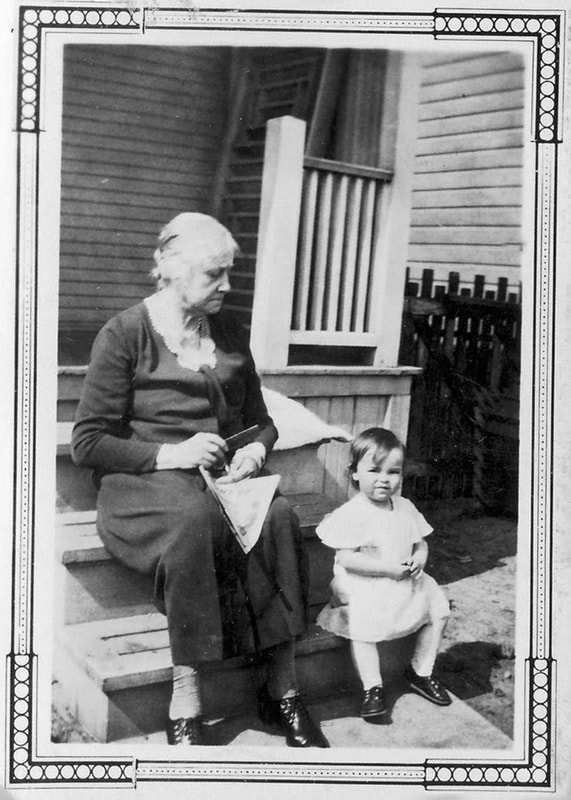

Avery Arthur Kenny was born 1885 in Brockville, Ontario and died 1959 in White Rock, BC (a suburb of Vancouver). The love of his life was Alice Blackburn, born in 1892 in Yorkshire, England and died in 1966 in Cloverdale, BC. Their daughter Agnes Irene Kenny was born in 1921 in Toronto, Ontario and died in 2014 in Armstrong, BC in the Okanagan Valley.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

b) - THE BEGINNING: Part 1

Avery and Alice Kenny met in Toronto, in 1912. Avery was working, for his father who was a dentist, when Alice came in as a patient. The following Saturday they met again at the ice rink. Avery drummed up the courage to ask Alice to skate with him. The gramophone blasted out the Blue Danube as they flew around the ice. When she invited Avery home for a hot drink after the rink closed for the night, her mother liked his quiet ways. Alice also liked him, and the friendship grew.

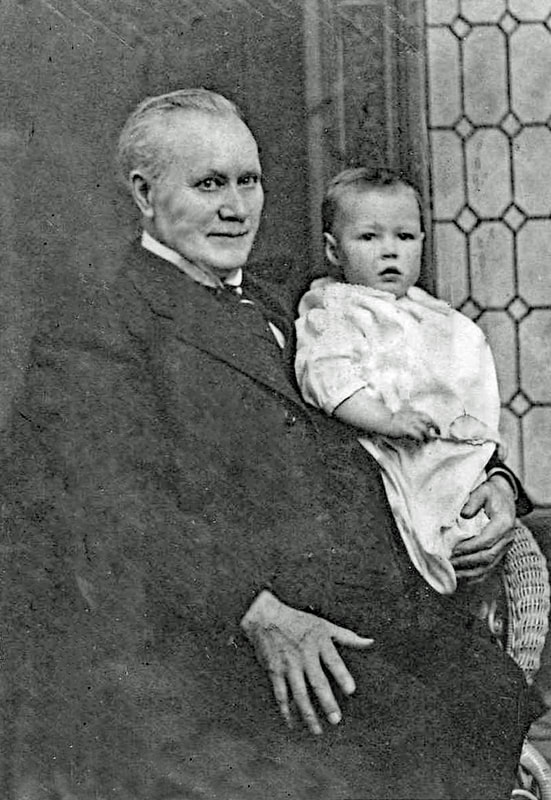

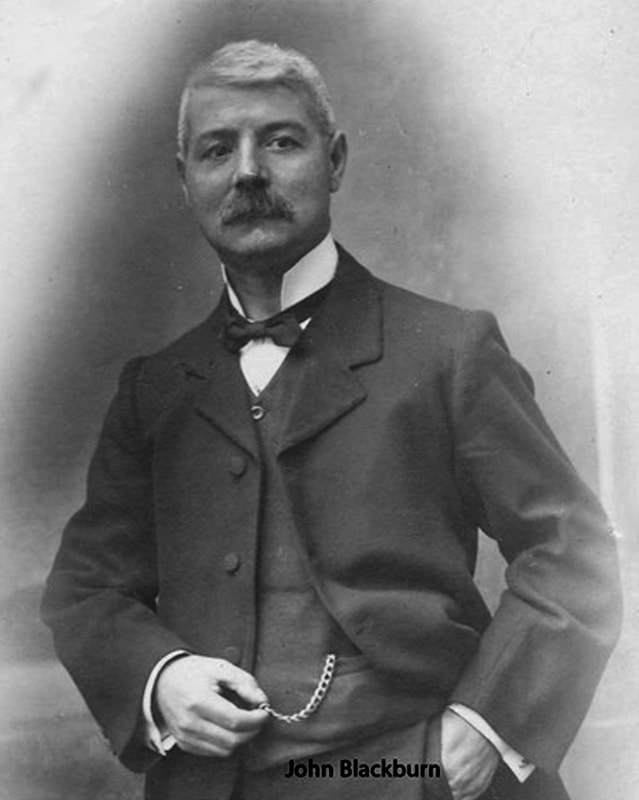

Alice worked as a seamstress for Black Brothers in Toronto, (who later became Tip-Top Tailors). She had immigrated to Canada when she was thirteen, from Leeds, Yorkshire, England, to Toronto, along with her parents and her sister. There, as a young girl, she helped her dad with the building of their home. She carried cement buckets and lumber along with her father whom she dearly loved. His pet name for her was "Bill". It was from her dad she inherited those flashing blue eyes, and fun loving ways.

With her lovely face, shining brown hair and those blue eyes, its no wonder Avery was attracted to her. Down the street was the Anglican Church, where Alice sang in the choir and taught a class of girls in Sunday School.

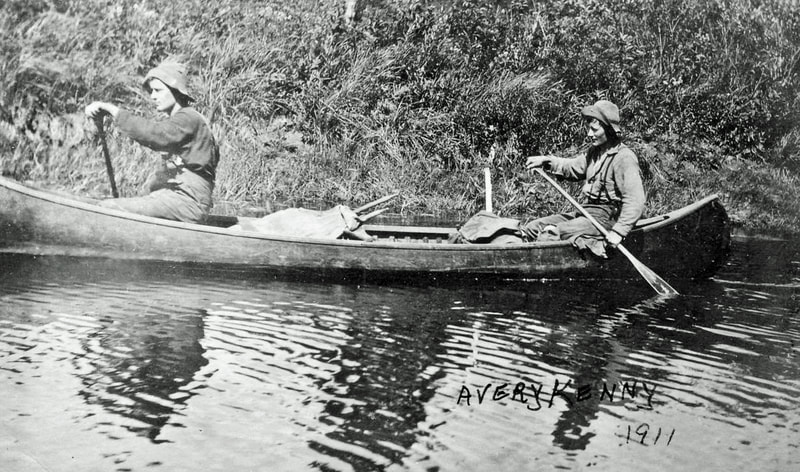

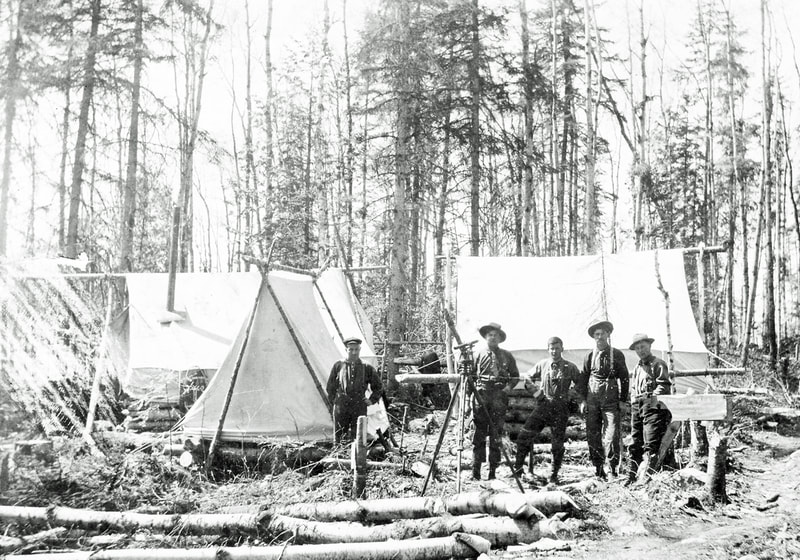

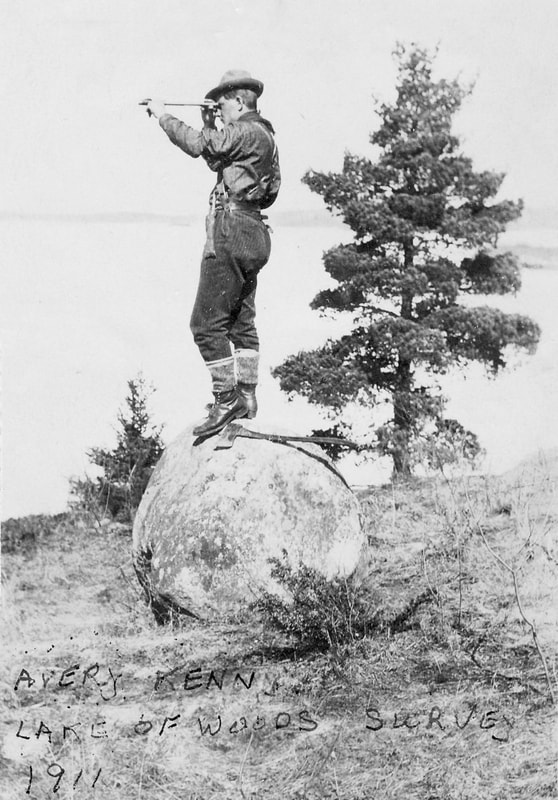

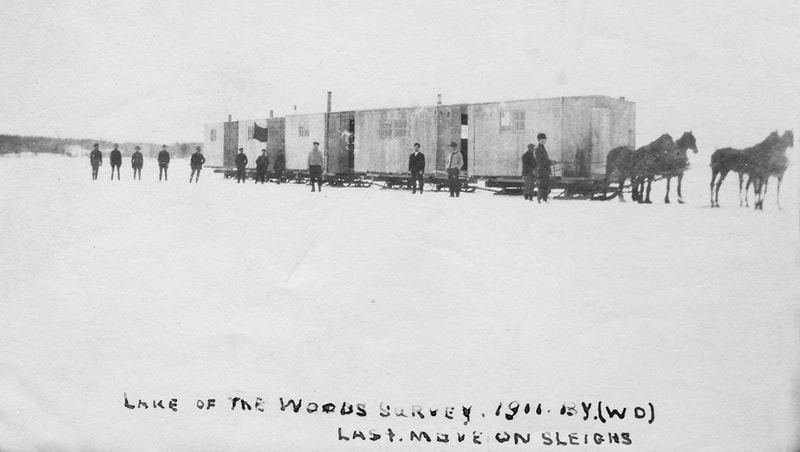

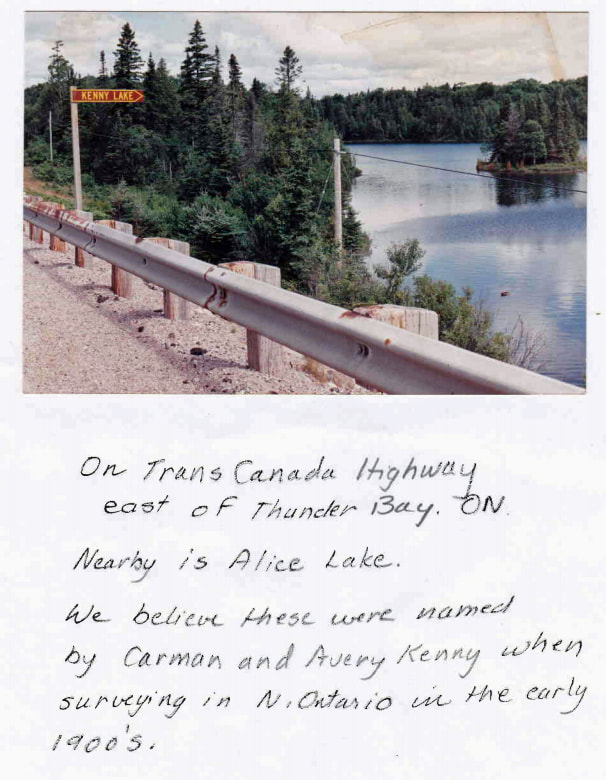

Avery spent his winters working as an apprentice for his father. The summers were spent in Northern Ontario on the survey with his brother, cooking for the crew. He learned how to bake beans and bread in the hot sand after the coals had been scraped away. Many the adventure he shared with Alice of portaging the canoes overland in rough spots, and shooting the rapids of the swift flowing streams. One island was named Alice Island, after the girl Avery was beginning to care for. His heart was happy when he found that she returned his love.

However, Avery had a dream. He had travelled west by rail years before, hitching rides in box cars. The call of the west was in his blood, and was continually on his mind. Now that he had found Alice, he decided to take his savings and head out to find a place to settle, and make a home for them.

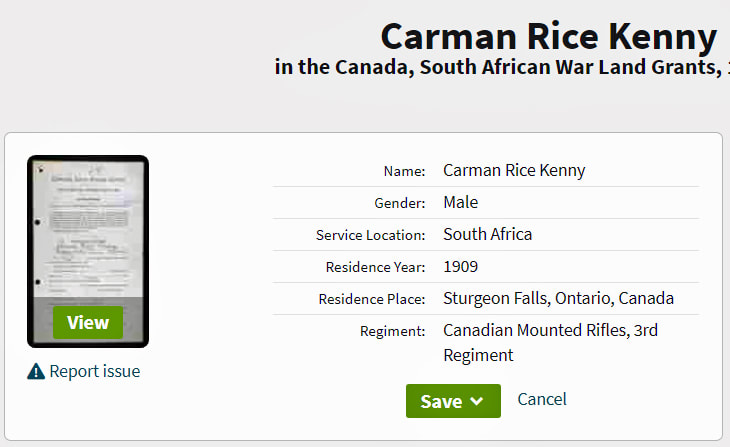

The Northwest was opening up. His brother had given him a South African War Grant that was not valid after July, 1913. He felt there was great opportunities for them in the west. He was strong, and he wasn't afraid of work. The future looked bright, and his sweetheart would wait for him.

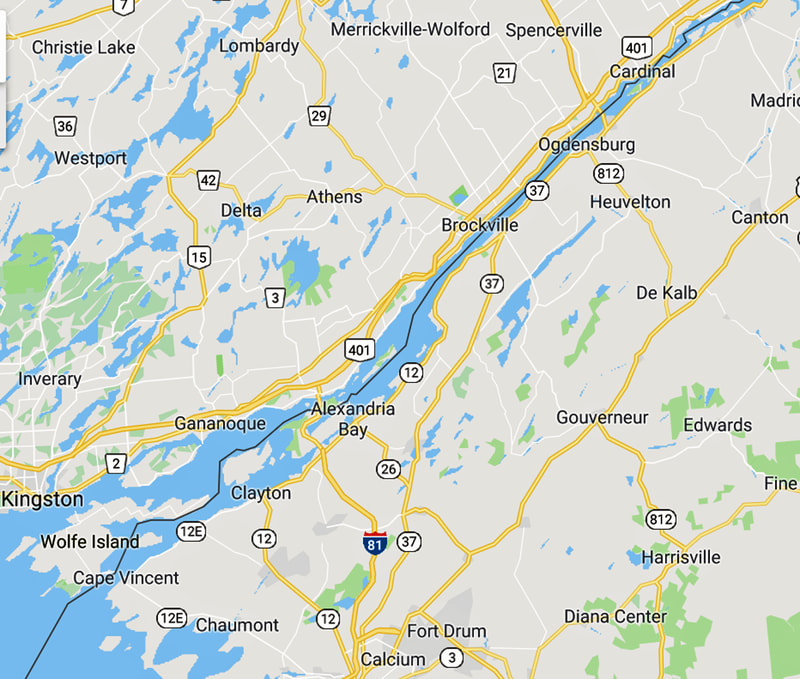

Avery's father, mother, and grandfather were born in Canada. His father's ancestors had originated in Ireland, and immigrated to Canada in the early 1800's, crossing the sea with a large family of thirteen children. They settled in the Ottawa area, at Gananoque.

Alice worked as a seamstress for Black Brothers in Toronto, (who later became Tip-Top Tailors). She had immigrated to Canada when she was thirteen, from Leeds, Yorkshire, England, to Toronto, along with her parents and her sister. There, as a young girl, she helped her dad with the building of their home. She carried cement buckets and lumber along with her father whom she dearly loved. His pet name for her was "Bill". It was from her dad she inherited those flashing blue eyes, and fun loving ways.

With her lovely face, shining brown hair and those blue eyes, its no wonder Avery was attracted to her. Down the street was the Anglican Church, where Alice sang in the choir and taught a class of girls in Sunday School.

Avery spent his winters working as an apprentice for his father. The summers were spent in Northern Ontario on the survey with his brother, cooking for the crew. He learned how to bake beans and bread in the hot sand after the coals had been scraped away. Many the adventure he shared with Alice of portaging the canoes overland in rough spots, and shooting the rapids of the swift flowing streams. One island was named Alice Island, after the girl Avery was beginning to care for. His heart was happy when he found that she returned his love.

However, Avery had a dream. He had travelled west by rail years before, hitching rides in box cars. The call of the west was in his blood, and was continually on his mind. Now that he had found Alice, he decided to take his savings and head out to find a place to settle, and make a home for them.

The Northwest was opening up. His brother had given him a South African War Grant that was not valid after July, 1913. He felt there was great opportunities for them in the west. He was strong, and he wasn't afraid of work. The future looked bright, and his sweetheart would wait for him.

Avery's father, mother, and grandfather were born in Canada. His father's ancestors had originated in Ireland, and immigrated to Canada in the early 1800's, crossing the sea with a large family of thirteen children. They settled in the Ottawa area, at Gananoque.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

c) - THE BEGINNING: Continued....

As a lad, Avery was forced to leave school in grade eight to help his mother keep the home together when his father and two older brothers were away in the Boer War and the South African War. He worked in a livery stable making fifty cents each week, which he brought home and gave to his mother and sister to provide food for the table. He kept five cents to buy a bag of peppermints, which he shared with the family.

Now he was heading out. The weather was balmy with winter break-up as he said goodbye to his saintly mother, who quietly tucked a Bible in with his belongings. Little did he know the lonely winter nights ahead when he would pore over it's pages while the wind raged around his one room log cabin in the North.

As his father said goodbye, he handed him a pair of forceps. "You never know when you might need them, son." Prophetic words indeed, for many a tooth was to be pulled with them in the years ahead.

When Avery said goodbye to Alice, they had no way of knowing it would be three long years, and World War l would be in force before they would meet again.

Now he was heading out. The weather was balmy with winter break-up as he said goodbye to his saintly mother, who quietly tucked a Bible in with his belongings. Little did he know the lonely winter nights ahead when he would pore over it's pages while the wind raged around his one room log cabin in the North.

As his father said goodbye, he handed him a pair of forceps. "You never know when you might need them, son." Prophetic words indeed, for many a tooth was to be pulled with them in the years ahead.

When Avery said goodbye to Alice, they had no way of knowing it would be three long years, and World War l would be in force before they would meet again.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

d) - THE EDSON TRAIL: Part 1

When Avery arrived in Edmonton, June 2, 1913, the first people he met was a couple of American farmers. One of them was named Carl Schliedge. After hearing tales of the great possibilities in the Peace River area, Avery made up his mind to go there. Carl decided to go with him.

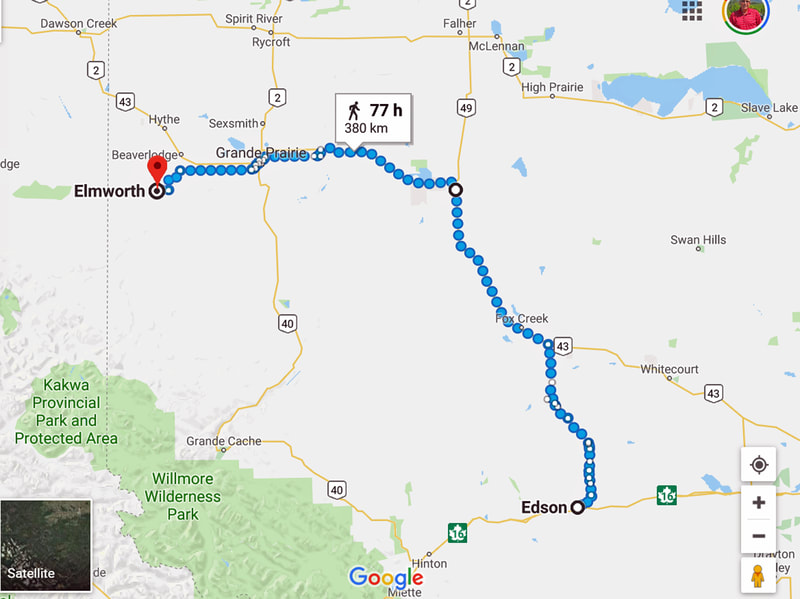

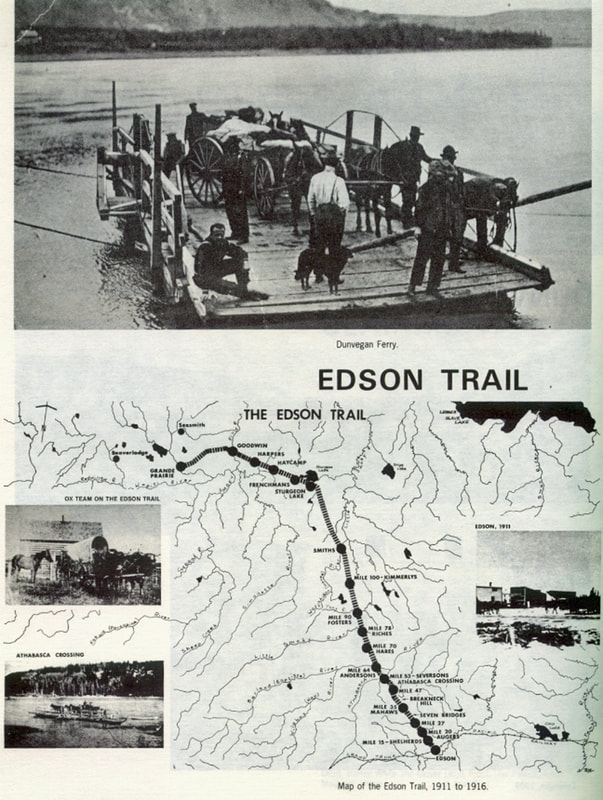

Avery bought a team of mules, whom he named Betsy and Darlene. He was to become famous as 'the kid with the mules'. They were the only mules in the country at that time, but Avery found they were strong, and quicker than horses. He bought a light wagon, with the mules in mind. It would not be too heavy for them to pull. Along with his grub-stake (food supplies), he bought a single walking plow. This plow was to tum the first sod south of the Red Willow River for a neighbour by the name of George Dumbeck. He set out the first week in June, 1913, and along with Carl, travelled first to Edson, then headed out over the Edson Trail.

In 1909, the Grand Trunk Railway was pushing its way slowly west from Edmonton to Jasper. Somewhere along the way there would have to be a jumping-off place for entering the Peace River Country. The people in Edson decided to start cutting a road through the bush, hoping the Government would finish it, and thus ensure that Edson would stay an important junction as the Peace opened up. It worked out, for the Government sent in an excellent engineer, A.H.MacGuire, who was to perform this task of cutting a passable road through the bush from Edson to Sturgeon Lake. Enterprising individuals went in to build stopping houses at many points along the trail. They cut hay in the meadows, brought in supplies, and provided rest and food for the weary, sometimes sick, oxen, horses and travellers.

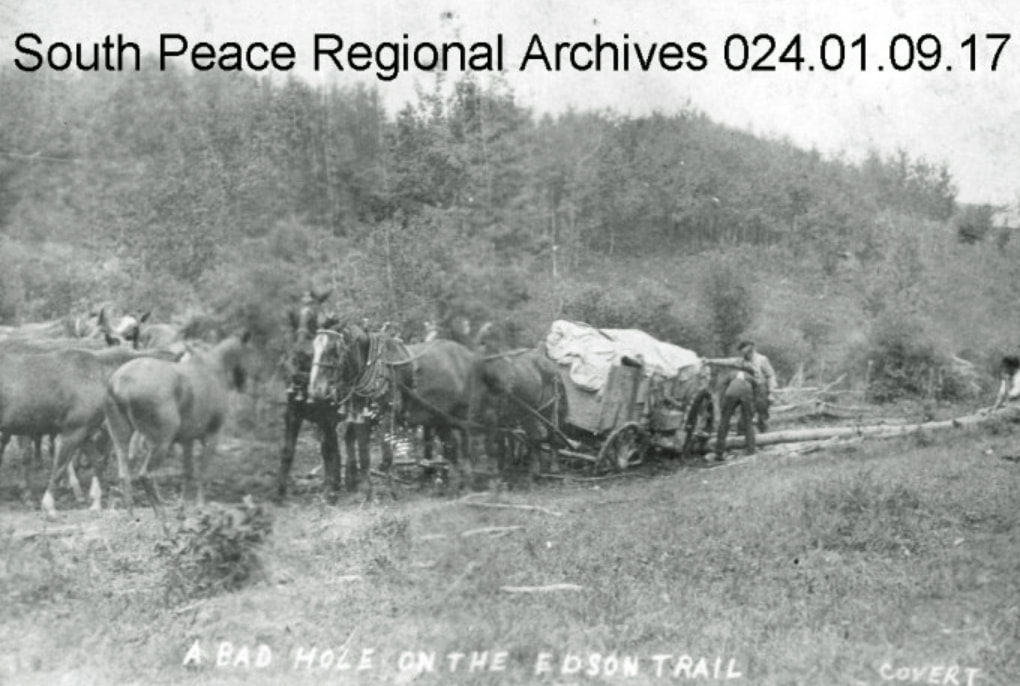

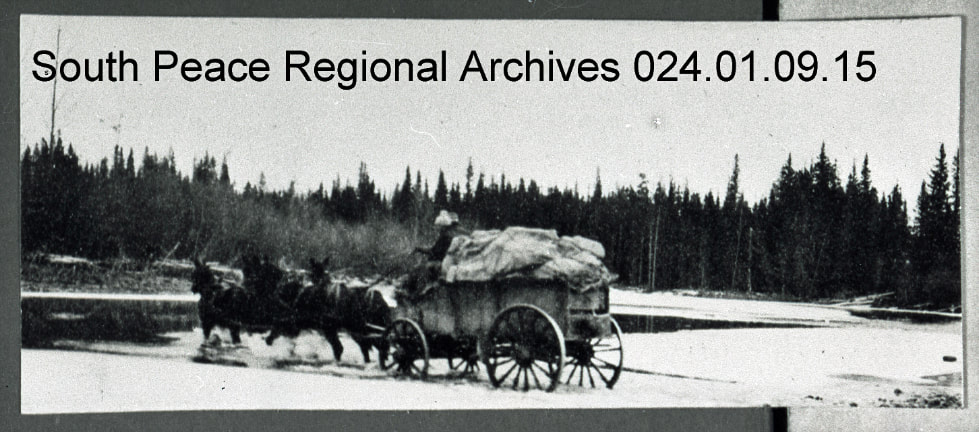

The Edson Trail was two hundred and fifty miles of mud, muskeg, and mosquitoes. In 1911 when it was built, it was the shortest route from the railway into the Grande Prairie region. It was used for only four years. During that time thousands of settlers travelled it, for they had heard about the fertile farm lands of Saskatoon Lake, Bear Lake, and the Beaverlodge area. Much of the road was over muskeg, (no bottom to it), where they laid miles of corduroy to make it passable. In the mud a wagon would sink in up to the axles and the oxen would be floundering in the mud up to their bellies. When they got stuck this way, there was nothing else to do but unload the wagon and carry the cargo piece by piece to the other side. This made countless trips with the precious load in the arms or on the back, sinking in mud up to the knees at every step. When all this hard work was accompanied by the hot sun, there was sure to be the mosquitoes and bull-flies adding to their torment.

If it was raining, (and it rained much of the time), then the matter was much worse, for it added to the mud problem. It also meant wet wood for the campfire, wet clothing, and untold misery. Some got discouraged and turned back. Those that went on, many of whom were women and children, had to take rest at odd times along the way. In some instances, it took three months to make the trip. The animals wore out and many died of fatigue or starvation, for feed and hay were very scarce. Some of the travellers were not able to buy feed, because of its scarcity, or lack of money. In that case, it was too bad, unless some kind soul took pity on them. Many people were compassionate, and if they had it to give, they would give.

In a few spots, there were meadows where the settlers often camped for as long as ten days to rest and feed their animals on the rich grass. One family had the misfortune to have a team of horses back off a bridge, and fall into the river. Another party of four men walked the two hundred miles with packs on their backs. A little English woman, Mary Ann O'Connell, was just two years out from city life in London. She was obliged to walk behind the ox-pulled wagon and carry her three week old baby as the jolting of the wagon made him sick. She was wearing high buttoned English boots, and the temperature was seventy or eighty degrees. When the baby became sick, they were forced to camp by Half-Way-River until he got well enough to go on. There were three brothers in the group, who were driving in a herd of cattle. As Mary Ann walked, the others in the party were able to travel much faster than her, so she ended up falling far behind. Perhaps it came as a relief when the wagons would get stuck, for that gave her the chance to catch up.

Avery bought a team of mules, whom he named Betsy and Darlene. He was to become famous as 'the kid with the mules'. They were the only mules in the country at that time, but Avery found they were strong, and quicker than horses. He bought a light wagon, with the mules in mind. It would not be too heavy for them to pull. Along with his grub-stake (food supplies), he bought a single walking plow. This plow was to tum the first sod south of the Red Willow River for a neighbour by the name of George Dumbeck. He set out the first week in June, 1913, and along with Carl, travelled first to Edson, then headed out over the Edson Trail.

In 1909, the Grand Trunk Railway was pushing its way slowly west from Edmonton to Jasper. Somewhere along the way there would have to be a jumping-off place for entering the Peace River Country. The people in Edson decided to start cutting a road through the bush, hoping the Government would finish it, and thus ensure that Edson would stay an important junction as the Peace opened up. It worked out, for the Government sent in an excellent engineer, A.H.MacGuire, who was to perform this task of cutting a passable road through the bush from Edson to Sturgeon Lake. Enterprising individuals went in to build stopping houses at many points along the trail. They cut hay in the meadows, brought in supplies, and provided rest and food for the weary, sometimes sick, oxen, horses and travellers.

The Edson Trail was two hundred and fifty miles of mud, muskeg, and mosquitoes. In 1911 when it was built, it was the shortest route from the railway into the Grande Prairie region. It was used for only four years. During that time thousands of settlers travelled it, for they had heard about the fertile farm lands of Saskatoon Lake, Bear Lake, and the Beaverlodge area. Much of the road was over muskeg, (no bottom to it), where they laid miles of corduroy to make it passable. In the mud a wagon would sink in up to the axles and the oxen would be floundering in the mud up to their bellies. When they got stuck this way, there was nothing else to do but unload the wagon and carry the cargo piece by piece to the other side. This made countless trips with the precious load in the arms or on the back, sinking in mud up to the knees at every step. When all this hard work was accompanied by the hot sun, there was sure to be the mosquitoes and bull-flies adding to their torment.

If it was raining, (and it rained much of the time), then the matter was much worse, for it added to the mud problem. It also meant wet wood for the campfire, wet clothing, and untold misery. Some got discouraged and turned back. Those that went on, many of whom were women and children, had to take rest at odd times along the way. In some instances, it took three months to make the trip. The animals wore out and many died of fatigue or starvation, for feed and hay were very scarce. Some of the travellers were not able to buy feed, because of its scarcity, or lack of money. In that case, it was too bad, unless some kind soul took pity on them. Many people were compassionate, and if they had it to give, they would give.

In a few spots, there were meadows where the settlers often camped for as long as ten days to rest and feed their animals on the rich grass. One family had the misfortune to have a team of horses back off a bridge, and fall into the river. Another party of four men walked the two hundred miles with packs on their backs. A little English woman, Mary Ann O'Connell, was just two years out from city life in London. She was obliged to walk behind the ox-pulled wagon and carry her three week old baby as the jolting of the wagon made him sick. She was wearing high buttoned English boots, and the temperature was seventy or eighty degrees. When the baby became sick, they were forced to camp by Half-Way-River until he got well enough to go on. There were three brothers in the group, who were driving in a herd of cattle. As Mary Ann walked, the others in the party were able to travel much faster than her, so she ended up falling far behind. Perhaps it came as a relief when the wagons would get stuck, for that gave her the chance to catch up.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

e) - THE EDSON TRAIL: Continued

Into the second week on the Trail they arrived at the Baptiste River, to find it was in flood, and no ferry. The men swam the oxen and cattle across. A raft was made for Mary Ann, who, with heart in her mouth and many prayers, I'm sure, got on board, and crossed the swollen swift running stream with her two little children clutched to her bosom. Her mother-in-law, who had come over from England with them, bravely stayed with the wagon as it was floated across the river. The top side boards on the wagon came off and floated away. Mary Ann's trunks with all of' her precious treasures, her rocking chair, and her only coat, floated down the stream. In the years to follow, this family had many a long lean year; but finally made their homesteads into fine, prosperous farms, with modern homes.

Another family ran into trouble when the husband broke his leg. The plucky little one hundred pound wife set the leg with home-made splints cut from the bush. That accomplished, she took over the team. This was done along with washing clothes beside the streams, cooking over the campfire, and keeping an eye on four active girls. It took four months for them to reach their destination.

Unfortunately, for many the Edson Trail did not tum out with a happy ending. The trip was especially hard for the women and children. Many children's and not a few settlers graves were dug beside some river, or along the Trail. As they travelled on, steep hills would cause problems, especially around the Athabaska River. There they often hitched two teams to one load in order to get to the top, or they would unload and make two or three trips with partial loads. At this section, many had to abandon the heavier and less useful of their belongings. A piano sat by the road at Mile 35 for a long time. Mowers and other farm machinery were left by the side of the road to be claimed again next year, or during the winter, when it would be easier to travel with the frost in the ground. People who travelled that trail were honest, no one ever reported losing anything they had left behind.

The Edson Trail was not used after 1916, when the railway arrived in the Grande Prairie country. Avery proudly cherished the memory of coming in over the Trail. His trip was not as hard as most, for they were travelling light. His wagon did not sink into the swamp as did the heavier loads. Often he would go around a crew who were stuck, and carry on his way. He had a July 1st deadline to file claim on his land. They arrived at the Big Smoky, and found a great number of people camped along the river as the ferry had a broken cable and had drifted down the river. The Government was supposed to come to repair it, but Avery couldn't wait. He and Carl decided to take the wagon apart and made a raft in order to float the supplies across. They crossed the river five times, and swam the mules across. While they were assembling their belongings and putting the wagon together, a young American boy drowned while swimming his horse across the river. He had been travelling with a family named Waldo, who settled a few miles from Avery's homestead. Mrs. Waldo was to later deliver Avery and Alice's children who were born in the log house along the Red Willow River.

The first letter Avery wrote to Alice from his piece of land was full of excitement for the future. Dated July 18, 1913:

"Well, I have filed, alight. I'll have a dandy place for you some day. I have a piece of river running through, lots of wood, and coal in a seam that runs along the river bank. There is A-1 land, lots of mountain trout and other kinds of fish. I am going to start drawing logs right away for a barn and a house. Write to me at Hillcourt, Alberta." (Halcourt)

Another family ran into trouble when the husband broke his leg. The plucky little one hundred pound wife set the leg with home-made splints cut from the bush. That accomplished, she took over the team. This was done along with washing clothes beside the streams, cooking over the campfire, and keeping an eye on four active girls. It took four months for them to reach their destination.

Unfortunately, for many the Edson Trail did not tum out with a happy ending. The trip was especially hard for the women and children. Many children's and not a few settlers graves were dug beside some river, or along the Trail. As they travelled on, steep hills would cause problems, especially around the Athabaska River. There they often hitched two teams to one load in order to get to the top, or they would unload and make two or three trips with partial loads. At this section, many had to abandon the heavier and less useful of their belongings. A piano sat by the road at Mile 35 for a long time. Mowers and other farm machinery were left by the side of the road to be claimed again next year, or during the winter, when it would be easier to travel with the frost in the ground. People who travelled that trail were honest, no one ever reported losing anything they had left behind.

The Edson Trail was not used after 1916, when the railway arrived in the Grande Prairie country. Avery proudly cherished the memory of coming in over the Trail. His trip was not as hard as most, for they were travelling light. His wagon did not sink into the swamp as did the heavier loads. Often he would go around a crew who were stuck, and carry on his way. He had a July 1st deadline to file claim on his land. They arrived at the Big Smoky, and found a great number of people camped along the river as the ferry had a broken cable and had drifted down the river. The Government was supposed to come to repair it, but Avery couldn't wait. He and Carl decided to take the wagon apart and made a raft in order to float the supplies across. They crossed the river five times, and swam the mules across. While they were assembling their belongings and putting the wagon together, a young American boy drowned while swimming his horse across the river. He had been travelling with a family named Waldo, who settled a few miles from Avery's homestead. Mrs. Waldo was to later deliver Avery and Alice's children who were born in the log house along the Red Willow River.

The first letter Avery wrote to Alice from his piece of land was full of excitement for the future. Dated July 18, 1913:

"Well, I have filed, alight. I'll have a dandy place for you some day. I have a piece of river running through, lots of wood, and coal in a seam that runs along the river bank. There is A-1 land, lots of mountain trout and other kinds of fish. I am going to start drawing logs right away for a barn and a house. Write to me at Hillcourt, Alberta." (Halcourt)

Editor's Note: Photos don't really bring the harshness of the Edson Trail trek into our life experiences today.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

f) - THE HOMESTEAD

Certainly his days ahead were full. Avery bought a team of oxen to help get out the logs for his buildings. One of the greatest blessings he had was Carl, who lived with him, and was a good hand with an axe. He could expertly trim the bark from the trees, making the top and bottom of each log flat. This way the logs would fit together and could be chinked up with river mud. On the long winter days and nights, Carl spent his time making bunks, chairs, table, and benches. One bench that stayed in the home for years had 'Alice' carved on the underside. You can be sure that wasn't Carl's work.

There was land to be cleared and hay to be cut for the animals for the winter ahead. It was too late to put in a garden. They ate lots of beans and rice.

There was land to be cleared and hay to be cut for the animals for the winter ahead. It was too late to put in a garden. They ate lots of beans and rice.

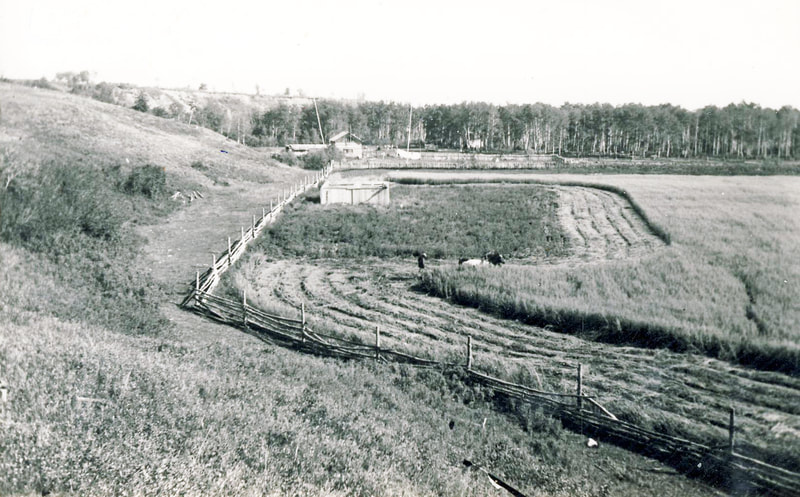

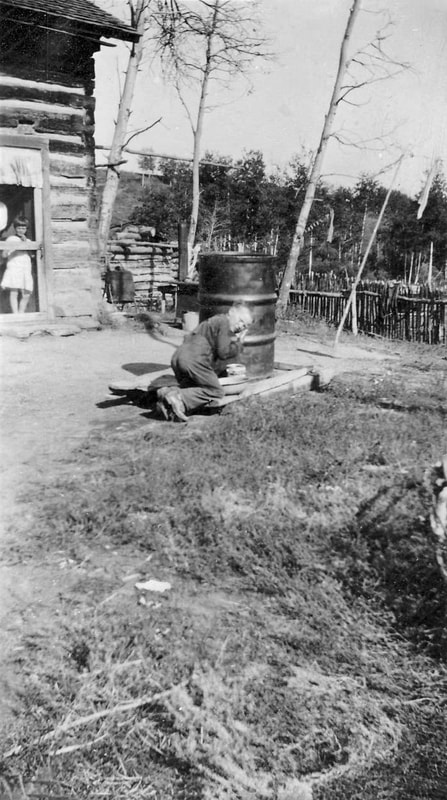

Editor's note: Let's think for a few moments what a log cabin with a sod roof and dirt floors was actually like; here are some images, the last one is the log house Avery built.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

g) - THE ANNUAL SPORTS DAY

On the following May 24, the countryside was humming with a big event. 'The Annual Sports Day', which was to be held at Beaverlodge, fifteen miles from Avery's farm. Avery had gone to Beaverlodge to ensure a colt for his mare the next spring and took in the big day. There was baseball, wrestling matches, foot races, bucking contests, and a concert at night. Anyone who could entertain at all had the go ahead.

Avery wrote to Alice about the crowd of two thousand people, and that he arrived home about 4 am. Did our hero go to bed? No sir! He had invited two families of friends to come to his place to fish! As soon as he arrived home, he started baking bread, stewing up dried apples and raisins, and got a batch of baked beans in the oven. The folks arrived at 9 am. Avery caught some fresh trout by lunch time, and with the other refreshments, they had a regular feast. To enjoy friends in that country was a God-send, and this was one of those occasions.

Avery wrote to Alice about the crowd of two thousand people, and that he arrived home about 4 am. Did our hero go to bed? No sir! He had invited two families of friends to come to his place to fish! As soon as he arrived home, he started baking bread, stewing up dried apples and raisins, and got a batch of baked beans in the oven. The folks arrived at 9 am. Avery caught some fresh trout by lunch time, and with the other refreshments, they had a regular feast. To enjoy friends in that country was a God-send, and this was one of those occasions.

h) - TRIALS AND REWARDS

After the guests had left, Avery checked out the sow he had bedded down in the barn, and found she was in the middle of her delivery. Not wanting any harm to come to her, he watched over her all night. In the morning she had six lively piglets. This pig was a real snoop. Avery had a fish line in the little river, and one day caught eighteen fish. Carl and Avery cleaned them and placed them in a wooden box in the river to keep them fresh. John, the 'sow, waded out in the river to the box. What she didn't eat of the fish, she let float away down the river. The men didn't care too much, because the next morning they caught another fifteen.

They woke up the next morning to find a new colt in the barn. Avery had four hens setting on fifteen eggs each. Spring was in the air. Neighbours moved into their house across the river, which Carl had built. Avery broke a piece of land for them with his small walking plow. Every spare minute in the summer months was spent clearing land with the oxen, burning brush, and picking rocks. By September 1914, he had forty tons of hay ready for his stock that winter.

Disaster, however, had struck the chickens. Out of one hundred chickens, the hawks had carried away forty-seven. They would swoop down and pluck them out of his open chicken run. Finally, they devised the idea to place poles cut from the woods across the top making a makeshift roof. One morning, on hearing a great noise from the chickens, Avery went out to find a hawk right inside the chicken run. He made short work of it.

That year, 1914, there was a killing frost in mid summer, and all the gardens were frozen. Avery wrote to Alice that Carl was smoking chewing tobacco because he had run out of cigarette tobacco. 'You ask me what I need the most? The answer is 'you'. He goes on to say: "When the river freezes over, I will drive the team along the ice and get some coal from the seam along the river bank." Twenty years later they were still using coal from that same seam.

Instead of the steep bank that was used by the settlers to travel up and down to the shallow river crossing, a grade was dug from the side of the hill that summer. It was hard work, all the extra dirt being dug out by a scoop. One of the neighbours helped him, and a small miracle happened on the day it was finished. Avery found a twenty dollar bill on the ground at the top of the grade. That was a lot of money in those days, and as he wasn't able to find out where it came from, he claimed it as payment for his work.

November 1914 he wrote to Alice about the many settlers who were having a hard time because of frozen gardens from the early frost. Because Alice had written worried about his welfare, he listed for her every scrap of food he had in the house. He must have recently made a trip over the Trail to get supplies, because here is what he had on hand: dry apples, thirty pounds, raisins, thirty pounds, cranberries, lots of them, dry saskatoons, rice, fifty pounds, lard, twenty five pounds, beans, fifty pounds, cornmeal, twenty pounds, oatmeal, ten pounds, pearl barley, flour, two hundred pounds, tea, sixteen pounds, coffee, ten pounds, sugar one hundred pounds, yeast cakes, candles. He told her sadly how a nail had poked a hole in a bag of sugar, causing it all to leak out along the Trail.

December 1, he wrote telling Alice how he had shot his first silver fox. He had spied it sitting in the moonlight on the frozen river bed. Taking good aim, he had nailed it where it sat. He skinned it, leaving the toe nails on, and sent it to his brother to sell.

They woke up the next morning to find a new colt in the barn. Avery had four hens setting on fifteen eggs each. Spring was in the air. Neighbours moved into their house across the river, which Carl had built. Avery broke a piece of land for them with his small walking plow. Every spare minute in the summer months was spent clearing land with the oxen, burning brush, and picking rocks. By September 1914, he had forty tons of hay ready for his stock that winter.

Disaster, however, had struck the chickens. Out of one hundred chickens, the hawks had carried away forty-seven. They would swoop down and pluck them out of his open chicken run. Finally, they devised the idea to place poles cut from the woods across the top making a makeshift roof. One morning, on hearing a great noise from the chickens, Avery went out to find a hawk right inside the chicken run. He made short work of it.

That year, 1914, there was a killing frost in mid summer, and all the gardens were frozen. Avery wrote to Alice that Carl was smoking chewing tobacco because he had run out of cigarette tobacco. 'You ask me what I need the most? The answer is 'you'. He goes on to say: "When the river freezes over, I will drive the team along the ice and get some coal from the seam along the river bank." Twenty years later they were still using coal from that same seam.

Instead of the steep bank that was used by the settlers to travel up and down to the shallow river crossing, a grade was dug from the side of the hill that summer. It was hard work, all the extra dirt being dug out by a scoop. One of the neighbours helped him, and a small miracle happened on the day it was finished. Avery found a twenty dollar bill on the ground at the top of the grade. That was a lot of money in those days, and as he wasn't able to find out where it came from, he claimed it as payment for his work.

November 1914 he wrote to Alice about the many settlers who were having a hard time because of frozen gardens from the early frost. Because Alice had written worried about his welfare, he listed for her every scrap of food he had in the house. He must have recently made a trip over the Trail to get supplies, because here is what he had on hand: dry apples, thirty pounds, raisins, thirty pounds, cranberries, lots of them, dry saskatoons, rice, fifty pounds, lard, twenty five pounds, beans, fifty pounds, cornmeal, twenty pounds, oatmeal, ten pounds, pearl barley, flour, two hundred pounds, tea, sixteen pounds, coffee, ten pounds, sugar one hundred pounds, yeast cakes, candles. He told her sadly how a nail had poked a hole in a bag of sugar, causing it all to leak out along the Trail.

December 1, he wrote telling Alice how he had shot his first silver fox. He had spied it sitting in the moonlight on the frozen river bed. Taking good aim, he had nailed it where it sat. He skinned it, leaving the toe nails on, and sent it to his brother to sell.

i) - HONEYMOON TRIP NORTH

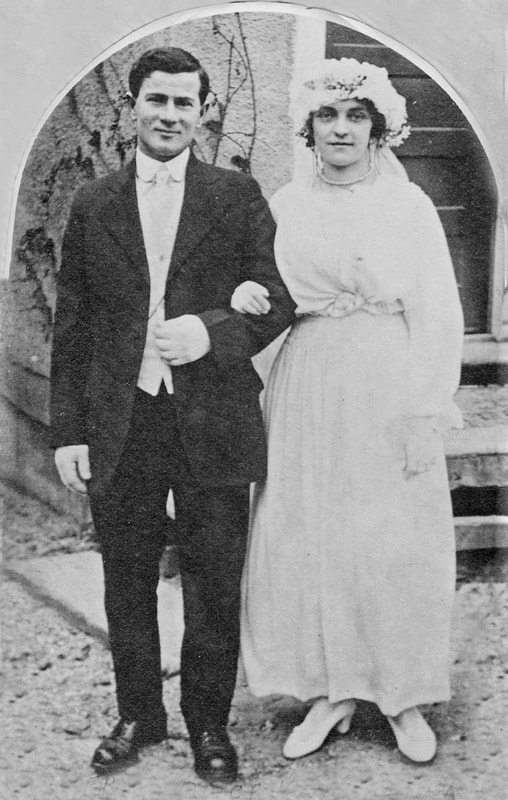

Towards the end of 1915, Avery went back to Toronto to be married to Alice. Another homesteader, named George Beadle, went East at the same time, also to be married.

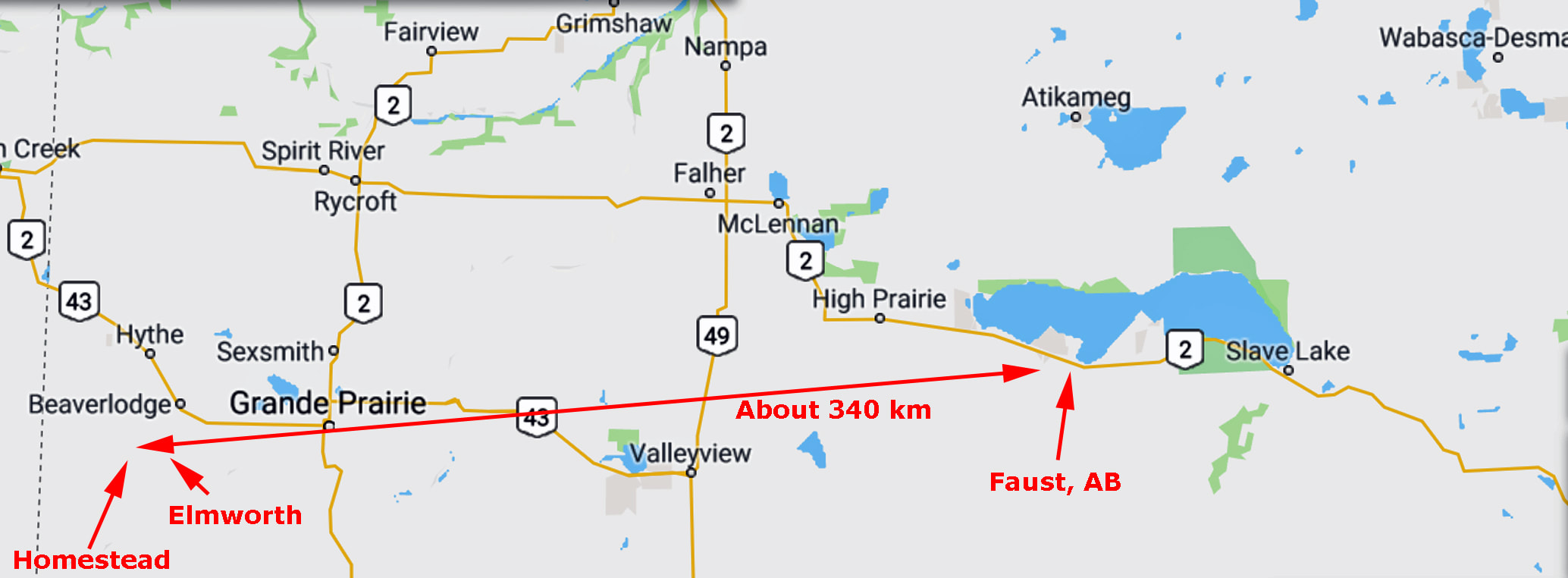

Alice tells of the return trip in January 1916. They met Sadie and George, the other young newly wed couple, at North Bay, and travelled together. It took three days to get to Edmonton, and three weeks to make the trip into the Peace River Country. The ED & BC Railway was in the process of being built. They took the first work train out of Edmonton. Avery had counted on the usual January Chinook wind from the Rockies for warmer weather, but that year there was no Chinook wind. It was fifty below zero, and a north wind blowing when they started out. As they chugged into Lesser Slave Lake, the train froze up.

The food ran out and there was no light or heat. The dozen or so passengers were taken to a fish camp along Slave Lake to eat and get warm while they sent to Smith for another engine. When the train arrived, this engine also froze up. They managed to get to McLennan with the next engine, where there was a hotel and a boarding house. The trainmen grabbed the hotel rooms, and Avery and Alice, George and Sadie, booked in at the boarding house. The women knew their men didn't have much money. More than once on the train they pretended not to be hungry when mealtime came around. Now, they made beds for a week for their keep; Alice said they had fun doing it. The story was told how Avery was ready to kill a man who had insulted her. Her comment on those days was, "I didn't know what I was headed into."

After a week at McLennan they got a chance to ride in the caboose on the train as far as the Smoke River. The settlement consisted of a few rough shacks. The mule team and Harry Brown, (a neighbour who was staying in Avery's cabin and looking after the stock while he was away), was supposed to meet them there. However, Avery's letter to Harry had not gotten through to him. They stayed at the Smoky for two days. The team didn't arrive, so they decided to take the work train when it went on to the end of the steel, which was two miles before Spirit River.

The weather was sixty below, with wind and drifting snow. Avery and George walked the two miles to see if the team was at Spirit River, but no team. It was two o'clock in the morning when they got the help of a neighbour, George White, who was at the train with a team and a flat deck on a hay rack. They hooked up the team, and drove to the train, where the girls and the luggage were loaded on. Everything went well until they reached a ravine, where going up the steep incline on the other side, girls, luggage, and all, slid off the flat deck into the snowbank. In the bitter cold, the horses fell down, and had to be unhitched. The luggage had to be carried to the top of the ravine, during which Avery froze his hands.

On reaching Spirit River, they stayed at the English and Caufman hotel. The next day George walked on to Spitfire Lake near Grande Prairie. He was gone for three days, and came back with a team. The group made it to Spitfire Lake the next day, and stayed at McLeans, where George and Sadie were going to work. Avery walked on to Lake Saskatoon the next day, and asked about his team. No team, but he found the letter at the post-office that he had written to Carl, asking him to have the team sent to meet him. Avery began the walk to Beaverlodge. He stopped at Jimmy Dixon's place, where Jimmy told him that Harry Brown had been at Lake Saskatoon that morning with the mule team.

Finally, Avery caught up to his team by walking back to Lake Saskatoon, where Matt Graham had stopped the team as Avery had instructed him to do if they should come along. He drove out for Alice at Spitfire Lake, and brought her to the McNaught's, four miles west of Beaverlodge. There they stayed overnight, eleven miles from home. The McNaught's had a big log house with a tent over the top, until they could get lumber for the roof. Alice played the piano that evening, much to Betty McNaught's delight.

They started out for the homestead the next morning. Harry Brown had been batching in the house while Avery was away. The log cabin, with a sod roof and dirt floor welcomed them home. Avery had brought a piece of glass for a window over the Edson Trail, which was an enormous feat, but Carl had broken it putting it in.

Alice tells of the return trip in January 1916. They met Sadie and George, the other young newly wed couple, at North Bay, and travelled together. It took three days to get to Edmonton, and three weeks to make the trip into the Peace River Country. The ED & BC Railway was in the process of being built. They took the first work train out of Edmonton. Avery had counted on the usual January Chinook wind from the Rockies for warmer weather, but that year there was no Chinook wind. It was fifty below zero, and a north wind blowing when they started out. As they chugged into Lesser Slave Lake, the train froze up.

The food ran out and there was no light or heat. The dozen or so passengers were taken to a fish camp along Slave Lake to eat and get warm while they sent to Smith for another engine. When the train arrived, this engine also froze up. They managed to get to McLennan with the next engine, where there was a hotel and a boarding house. The trainmen grabbed the hotel rooms, and Avery and Alice, George and Sadie, booked in at the boarding house. The women knew their men didn't have much money. More than once on the train they pretended not to be hungry when mealtime came around. Now, they made beds for a week for their keep; Alice said they had fun doing it. The story was told how Avery was ready to kill a man who had insulted her. Her comment on those days was, "I didn't know what I was headed into."

After a week at McLennan they got a chance to ride in the caboose on the train as far as the Smoke River. The settlement consisted of a few rough shacks. The mule team and Harry Brown, (a neighbour who was staying in Avery's cabin and looking after the stock while he was away), was supposed to meet them there. However, Avery's letter to Harry had not gotten through to him. They stayed at the Smoky for two days. The team didn't arrive, so they decided to take the work train when it went on to the end of the steel, which was two miles before Spirit River.

The weather was sixty below, with wind and drifting snow. Avery and George walked the two miles to see if the team was at Spirit River, but no team. It was two o'clock in the morning when they got the help of a neighbour, George White, who was at the train with a team and a flat deck on a hay rack. They hooked up the team, and drove to the train, where the girls and the luggage were loaded on. Everything went well until they reached a ravine, where going up the steep incline on the other side, girls, luggage, and all, slid off the flat deck into the snowbank. In the bitter cold, the horses fell down, and had to be unhitched. The luggage had to be carried to the top of the ravine, during which Avery froze his hands.

On reaching Spirit River, they stayed at the English and Caufman hotel. The next day George walked on to Spitfire Lake near Grande Prairie. He was gone for three days, and came back with a team. The group made it to Spitfire Lake the next day, and stayed at McLeans, where George and Sadie were going to work. Avery walked on to Lake Saskatoon the next day, and asked about his team. No team, but he found the letter at the post-office that he had written to Carl, asking him to have the team sent to meet him. Avery began the walk to Beaverlodge. He stopped at Jimmy Dixon's place, where Jimmy told him that Harry Brown had been at Lake Saskatoon that morning with the mule team.

Finally, Avery caught up to his team by walking back to Lake Saskatoon, where Matt Graham had stopped the team as Avery had instructed him to do if they should come along. He drove out for Alice at Spitfire Lake, and brought her to the McNaught's, four miles west of Beaverlodge. There they stayed overnight, eleven miles from home. The McNaught's had a big log house with a tent over the top, until they could get lumber for the roof. Alice played the piano that evening, much to Betty McNaught's delight.

They started out for the homestead the next morning. Harry Brown had been batching in the house while Avery was away. The log cabin, with a sod roof and dirt floor welcomed them home. Avery had brought a piece of glass for a window over the Edson Trail, which was an enormous feat, but Carl had broken it putting it in.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

j) - ALICE TAKES UP THE TASK

The cabin needed cleaning, and the next morning Alice set to it. When she discovered a pail hanging from the roof with some queer, strange smelling stuff in it, she promptly threw it out. She had thrown out the sour-dough with which they had the starter for their bread. They lived on biscuits until they got to a neighbour to beg another batch. Not used to farm life, she thought the cream she was whipping had gone bad when it turned into butter, so she threw that out too. She was so pleased with the eggs the hens laid, at the beginning she gathered them one at a time, as they were produced.

Two weeks after she arrived, the minister rode out from Beaverlodge on horseback to see if they would have church in their home. For twelve years, once a month, this became a regular event.

Neighbours came, and many stayed for supper. Later, in the larger house, there would be two people sitting on each step that led upstairs, while others packed the plank seats Avery had made ready before the services. Alice played a suitcase organ in the early days, pumping, playing, and singing, often with a baby on her knee. Once she did all this with her eye on a hawk that was circling over the chicken pen, ready to strike. Sometimes she would sing a solo in her beautiful soprano voice. The one most remembered by Irene was;

There were ninety and nine that safely lay,

In the shelter of the fold;

But one was out on the hills away,

Far off from the gates of gold--

ln later years, Avery's mother passed away, and left her piano to Irene, who was the fourth child. It was shipped by train to Grande Prairie, where the horses ran away with it in the wagon. It wasn't back in tune again for a year, when a piano tuner unannounced rode into the yard.

Two weeks after she arrived, the minister rode out from Beaverlodge on horseback to see if they would have church in their home. For twelve years, once a month, this became a regular event.

Neighbours came, and many stayed for supper. Later, in the larger house, there would be two people sitting on each step that led upstairs, while others packed the plank seats Avery had made ready before the services. Alice played a suitcase organ in the early days, pumping, playing, and singing, often with a baby on her knee. Once she did all this with her eye on a hawk that was circling over the chicken pen, ready to strike. Sometimes she would sing a solo in her beautiful soprano voice. The one most remembered by Irene was;

There were ninety and nine that safely lay,

In the shelter of the fold;

But one was out on the hills away,

Far off from the gates of gold--

ln later years, Avery's mother passed away, and left her piano to Irene, who was the fourth child. It was shipped by train to Grande Prairie, where the horses ran away with it in the wagon. It wasn't back in tune again for a year, when a piano tuner unannounced rode into the yard.

k) - THE FAMILY BEGINS

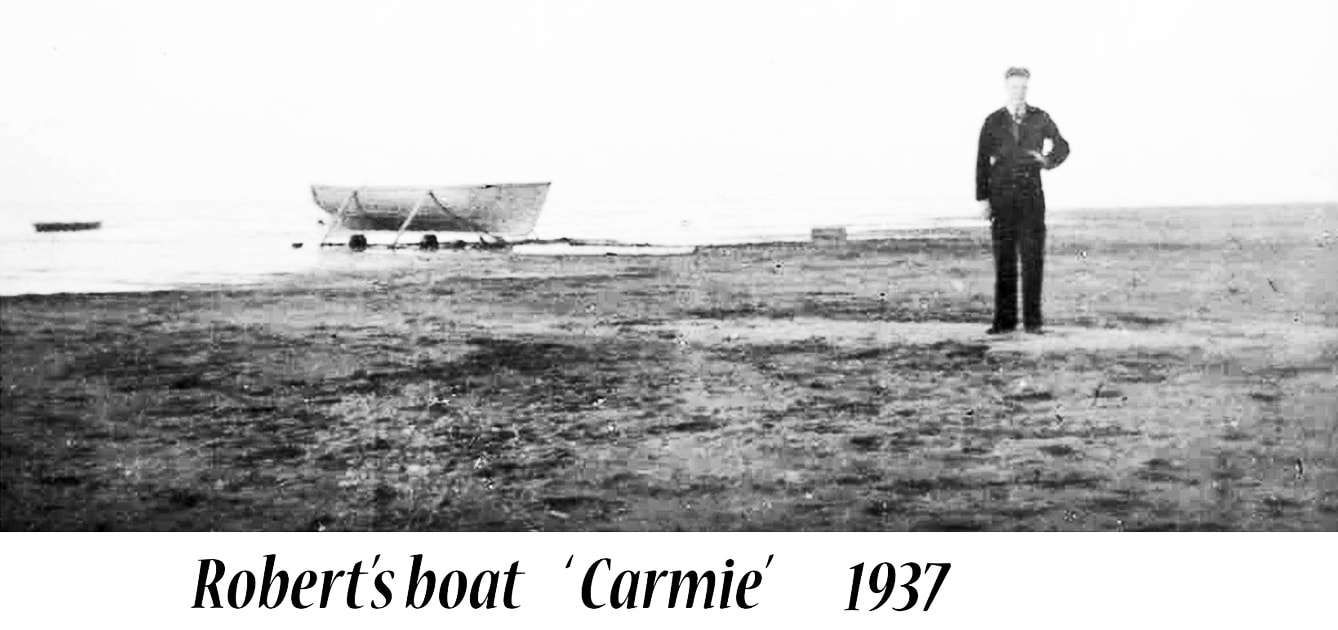

Robert was born in November 1916, on the homestead, with a neighbour, Mrs. Waldo, as mid-wife. She also assisted when Eddie and Arthur were born, but Arthur was a difficult breach birth. Alice nearly died bringing him into the world. She swore she would never have another baby without a Dr's. attention.

In 1917, homesteaders started coming into the North country in earnest. They brought their blankets, and as many as fourteen slept overnight in the barn. 1918 was a long, hard winter, bitterly cold.

When Irene was expected in 1921, Alice took the train to Toronto along with the three boys, in order that the baby could be born there. Arthur wasn't yet two years old, and had been sick with Bronchial Pneumonia in the spring. The little mother had to carry him every step of the way, plus look after two other rambunctious boys. It was disastrous when Eddie threw the towel and soap out of the train window.

She stayed in Toronto for six months. Irene was born in Grandmother and Grandfather Blackburn's house. Alice was happy to have a little girl. It was a temptation for her never to in back to the hardship of the farm, but feeling she would be a burden to her mother and dad, she returned home in the spring. Looking back years later, she realized if she had not gone back, Avery would have come East to her.

Marion was born in 1922, Carman in 1929, and George in 1935.

In 1917, homesteaders started coming into the North country in earnest. They brought their blankets, and as many as fourteen slept overnight in the barn. 1918 was a long, hard winter, bitterly cold.

When Irene was expected in 1921, Alice took the train to Toronto along with the three boys, in order that the baby could be born there. Arthur wasn't yet two years old, and had been sick with Bronchial Pneumonia in the spring. The little mother had to carry him every step of the way, plus look after two other rambunctious boys. It was disastrous when Eddie threw the towel and soap out of the train window.

She stayed in Toronto for six months. Irene was born in Grandmother and Grandfather Blackburn's house. Alice was happy to have a little girl. It was a temptation for her never to in back to the hardship of the farm, but feeling she would be a burden to her mother and dad, she returned home in the spring. Looking back years later, she realized if she had not gone back, Avery would have come East to her.

Marion was born in 1922, Carman in 1929, and George in 1935.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

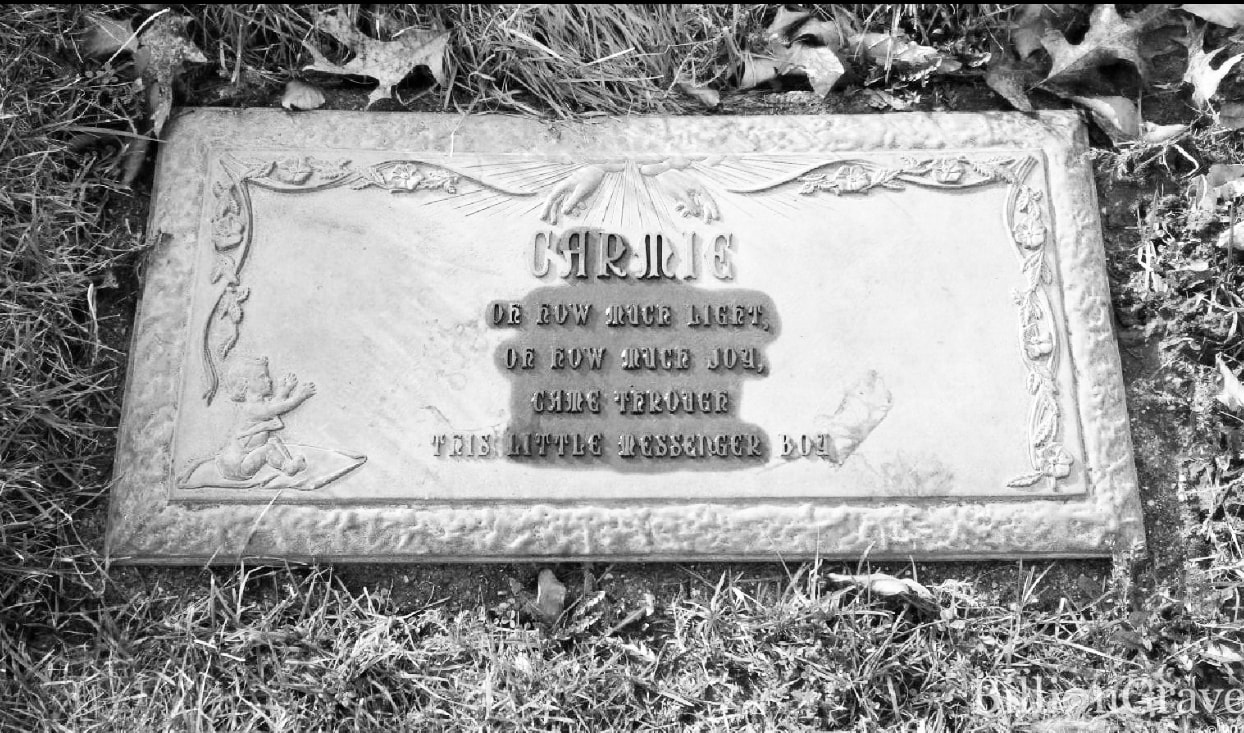

l) - CARMIE'S STORY

It was Christmas Eve. The boys had gone to the woods to cut down a tree tall enough to stand to the roof. The girls and Arthur and Carman had hung up their stockings and were off to bed. Alice and Avery and Robert and Eddy were hanging the cherished decorations on the tree, and putting candies into the stockings. Suddenly, Alice developed pains in her chest, and Avery carried her to bed. Her sickness turned out to be pneumonia, and she was confined to bed. On Christmas morning, Robert was sick.

Carman rode his new bicycle round and round the tree, and often went to his mother to give her his little smile and words of comfort. Two days later, Carman was dressed, and when he had finished his breakfast, he asked to go play with his little six year old playmate, Alvin. They had sleigh rides down the hills, and he came to the kitchen door smiling and happy, covered with snow. Avery was on his way out to the barn to catch a turkey to dress for New Years. As he met Avery, Carman looked up at him and said, "Daddy, you tell them that Jesus knows how."

In an off handed way, Avery said that he would, and let it go at that. Carmie went with his dad, and they got two turkeys, one for the minister, Rev. Harrison, and one for the family. That was Monday night, and Carman died on Wednesday night. He had pneumonia, and was taken suddenly from the family. As the last little breath left his body, Avery unfolded his heart to God. On his knees, he said, "Oh God, forgive me. I understand he is a messenger," and as he said that, the words: "A little child shall lead them" rang in his brain. He could hear his mother

singing it. Alice was calling for her little sunny boy to come back, but the little one was gone.

When it came to the burial, Alice requested the little boy be buried close to her. Avery waded out in the deep snow and found a place beneath the poplar trees where Carman used to play. He had to take a pickaxe to dig the frozen soil. When he returned and told Alice where they were going to place him, the mother was comforted to know he would be close. The funeral was held in the farm house, with the neighbours surrounding the grieving family. Alice was still in the sick bed. One little sister sat on the steps leading up to her mother's bedroom, and heard for the first time that wonderful old hymn:

Safe in the arms of Jesus,

Safe on His tender breast,

There by His love o'er shaded,

Sweetly my soul shall rest.

During the next few days, Avery could not rest. In his mind were the words: "A little child shall lead them." He wanted to find out whether it was in the scriptures. He looked through the Bible but he couldn't find it. With tears in his eyes, he went to the Dumbecks, who lived across the river. Together they looked, but could not find it. Then they told him what Carman has said before he left for home the evening he was playing on the hillside with Alvin. Suddenly he had stopped playing, and trembling he said,"! must go home, Jesus is coming for me." He went straight home. Jesus did come for him two days later.

Avery trudged his way across the frozen river, pondering the new events he had just heard. Telling Alice about it helped a little, but he was determined to find out if the words: "A little child shall lead them" was in the Bible. Avery got out the team and the sleigh with the wheat box. Driving to the granary, he shovelled on a load of grain. It was stormy and cold. The roads were full of drifts, but he headed for Beaverlodge, sixteen miles away.

Upon arrival at the grain elevator, he unloaded the grain and cared for his team, then headed for Rev. Harrison's residence, and told him what Carnan had said. Avery said: "Can you help me find out if there is such a scripture as "A little child shall lead them?" Immediately, Rev. Harrison opened the Bible, and there it was: Isaiah 11;16. Rejoicing, he could hardly wait to get home to tell Alice, but he continued to wonder how "The little child shall lead them." He wanted to study, so he went to the neighbour again, who gave him a book called Watchtower, saying it might help him. Avery could not make head or tail of it. Feeling he must go to the Bible again, he took his Bible down. At that very sitting, in a book of so many pages, he turned to Mark 9;37: And Jesus called a little child unto Him, and set him in the midst of them, and said: "Verily l say unto you, except ye become converted and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven."

Now Avery understood. It was God who spoke to him on the doorstep, and he didn't understand. It was God who spoke to him when the child was dead, and he understood. "Has the world got to die to understand?" he thought. No, Avery decided, God was with him in the message he had received. As he wrote it down, he tells that God wanted him to convey that message to the world, and his little son had come as a messenger to explain it to him; It had to do with the faith, love, friendship and truth that can be found in little children. God has put the little child into every home in some way. Let them be our guide, Avery writes. Take the little child that creeps the floor, look into his or her eyes, see the love, the friendship and trust as they put their arms about your neck and cling. Look at the faith they have in us. Would you not want to live in a word like this?

This is what God means in the message. Unless we be converted and become as a little child we cannot have peace on earth and goodwill towards men. Neither can there be peace in the home, in the churches, among the nations. Jesus explained it to His disciples, when He spoke about the children. Carman explained it to Avery when he told him, "Daddy you tell them that Jesus knows how." Love through Jesus Christ is the answer. We can only achieve this by pulling together.

Avery was concerned how he would be able to give out the message he believed God had given him for the world. One afternoon Alice came home from the Ladies Aid Meeting, and told Avery the news that the women wanted to honour him with a picnic because they considered him to be the senior pioneer in the area. It was to be the first Old Timers Picnic. Alice and Avery invited them to have the picnic at their place, to be held July 3, 1933. That would be exactly twenty years to the day that Avery had set foot on the soil of his homestead there along the Red Willow River. Avery arranged the program, with foot-races, horse shoe tossing, basketball, baseball, and speeches. Everyone was to bring a picnic lunch to be shared together. Avery was asked to share about their pioneer days. One Sunday afternoon he sat down to write out his speech.

Alice had gone to church with the children. The house was quiet. Avery looked out the kitchen window towards the tall poplar trees which threw their shadow across the little grave. He planned to tell Carmie's message somehow. He would start with his story about the early days, the trip over the Trail, and lead into Carman's story, which was so near to his heart. However, he felt inadequate about it, he knew every time he mentioned the little boy's name, Alice would start to cry. That was his greatest concern. Therefore he arranged that Rev. Harrison should tell that part of the speech. He gave the minister all the details, and felt relieved. To the family's great joy, Alice's mother came to visit them for the first time. Avery thought God had arranged it, so Alice could have comfort when Carmie's story was told.

The day of the picnic dawned clear and warm. It seemed the whole countryside began arriving at the farm house. Some drove down the hill, others crossed the river from the Elmworth area, with cars, on horseback, or with wagons and Bennett Buggies (wagons with rubber wheels for easier ride.). Approximately three hundred people attended. One hour before people were to arrive, a message came that Rev. Harrison could not attend because he was sick. Avery prepared as best he could with the little time he had. His speech went well, until he came to Carman's message he wanted to share to the world. He knew God understood he could not speak because of his emotions.

That is the reason why, twenty five years later, as he lay in the hospital suffering from a very serious heart attack, he said to his oldest daughter, "Renie, our life story should be told, I know you will do it." I have endeavoured to tell it, and l am glad.

Carman rode his new bicycle round and round the tree, and often went to his mother to give her his little smile and words of comfort. Two days later, Carman was dressed, and when he had finished his breakfast, he asked to go play with his little six year old playmate, Alvin. They had sleigh rides down the hills, and he came to the kitchen door smiling and happy, covered with snow. Avery was on his way out to the barn to catch a turkey to dress for New Years. As he met Avery, Carman looked up at him and said, "Daddy, you tell them that Jesus knows how."

In an off handed way, Avery said that he would, and let it go at that. Carmie went with his dad, and they got two turkeys, one for the minister, Rev. Harrison, and one for the family. That was Monday night, and Carman died on Wednesday night. He had pneumonia, and was taken suddenly from the family. As the last little breath left his body, Avery unfolded his heart to God. On his knees, he said, "Oh God, forgive me. I understand he is a messenger," and as he said that, the words: "A little child shall lead them" rang in his brain. He could hear his mother

singing it. Alice was calling for her little sunny boy to come back, but the little one was gone.

When it came to the burial, Alice requested the little boy be buried close to her. Avery waded out in the deep snow and found a place beneath the poplar trees where Carman used to play. He had to take a pickaxe to dig the frozen soil. When he returned and told Alice where they were going to place him, the mother was comforted to know he would be close. The funeral was held in the farm house, with the neighbours surrounding the grieving family. Alice was still in the sick bed. One little sister sat on the steps leading up to her mother's bedroom, and heard for the first time that wonderful old hymn:

Safe in the arms of Jesus,

Safe on His tender breast,

There by His love o'er shaded,

Sweetly my soul shall rest.

During the next few days, Avery could not rest. In his mind were the words: "A little child shall lead them." He wanted to find out whether it was in the scriptures. He looked through the Bible but he couldn't find it. With tears in his eyes, he went to the Dumbecks, who lived across the river. Together they looked, but could not find it. Then they told him what Carman has said before he left for home the evening he was playing on the hillside with Alvin. Suddenly he had stopped playing, and trembling he said,"! must go home, Jesus is coming for me." He went straight home. Jesus did come for him two days later.

Avery trudged his way across the frozen river, pondering the new events he had just heard. Telling Alice about it helped a little, but he was determined to find out if the words: "A little child shall lead them" was in the Bible. Avery got out the team and the sleigh with the wheat box. Driving to the granary, he shovelled on a load of grain. It was stormy and cold. The roads were full of drifts, but he headed for Beaverlodge, sixteen miles away.

Upon arrival at the grain elevator, he unloaded the grain and cared for his team, then headed for Rev. Harrison's residence, and told him what Carnan had said. Avery said: "Can you help me find out if there is such a scripture as "A little child shall lead them?" Immediately, Rev. Harrison opened the Bible, and there it was: Isaiah 11;16. Rejoicing, he could hardly wait to get home to tell Alice, but he continued to wonder how "The little child shall lead them." He wanted to study, so he went to the neighbour again, who gave him a book called Watchtower, saying it might help him. Avery could not make head or tail of it. Feeling he must go to the Bible again, he took his Bible down. At that very sitting, in a book of so many pages, he turned to Mark 9;37: And Jesus called a little child unto Him, and set him in the midst of them, and said: "Verily l say unto you, except ye become converted and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven."

Now Avery understood. It was God who spoke to him on the doorstep, and he didn't understand. It was God who spoke to him when the child was dead, and he understood. "Has the world got to die to understand?" he thought. No, Avery decided, God was with him in the message he had received. As he wrote it down, he tells that God wanted him to convey that message to the world, and his little son had come as a messenger to explain it to him; It had to do with the faith, love, friendship and truth that can be found in little children. God has put the little child into every home in some way. Let them be our guide, Avery writes. Take the little child that creeps the floor, look into his or her eyes, see the love, the friendship and trust as they put their arms about your neck and cling. Look at the faith they have in us. Would you not want to live in a word like this?

This is what God means in the message. Unless we be converted and become as a little child we cannot have peace on earth and goodwill towards men. Neither can there be peace in the home, in the churches, among the nations. Jesus explained it to His disciples, when He spoke about the children. Carman explained it to Avery when he told him, "Daddy you tell them that Jesus knows how." Love through Jesus Christ is the answer. We can only achieve this by pulling together.

Avery was concerned how he would be able to give out the message he believed God had given him for the world. One afternoon Alice came home from the Ladies Aid Meeting, and told Avery the news that the women wanted to honour him with a picnic because they considered him to be the senior pioneer in the area. It was to be the first Old Timers Picnic. Alice and Avery invited them to have the picnic at their place, to be held July 3, 1933. That would be exactly twenty years to the day that Avery had set foot on the soil of his homestead there along the Red Willow River. Avery arranged the program, with foot-races, horse shoe tossing, basketball, baseball, and speeches. Everyone was to bring a picnic lunch to be shared together. Avery was asked to share about their pioneer days. One Sunday afternoon he sat down to write out his speech.

Alice had gone to church with the children. The house was quiet. Avery looked out the kitchen window towards the tall poplar trees which threw their shadow across the little grave. He planned to tell Carmie's message somehow. He would start with his story about the early days, the trip over the Trail, and lead into Carman's story, which was so near to his heart. However, he felt inadequate about it, he knew every time he mentioned the little boy's name, Alice would start to cry. That was his greatest concern. Therefore he arranged that Rev. Harrison should tell that part of the speech. He gave the minister all the details, and felt relieved. To the family's great joy, Alice's mother came to visit them for the first time. Avery thought God had arranged it, so Alice could have comfort when Carmie's story was told.

The day of the picnic dawned clear and warm. It seemed the whole countryside began arriving at the farm house. Some drove down the hill, others crossed the river from the Elmworth area, with cars, on horseback, or with wagons and Bennett Buggies (wagons with rubber wheels for easier ride.). Approximately three hundred people attended. One hour before people were to arrive, a message came that Rev. Harrison could not attend because he was sick. Avery prepared as best he could with the little time he had. His speech went well, until he came to Carman's message he wanted to share to the world. He knew God understood he could not speak because of his emotions.

That is the reason why, twenty five years later, as he lay in the hospital suffering from a very serious heart attack, he said to his oldest daughter, "Renie, our life story should be told, I know you will do it." I have endeavoured to tell it, and l am glad.

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

Editor's Note: Family member memories often differ from person to person, and they do in the case of Carmie's Story.

Right click on Download File and open in a new Tab:

Right click on Download File and open in a new Tab:

| the_story_of_carman_kenny.pdf | |

| File Size: | 18 kb |

| File Type: | |

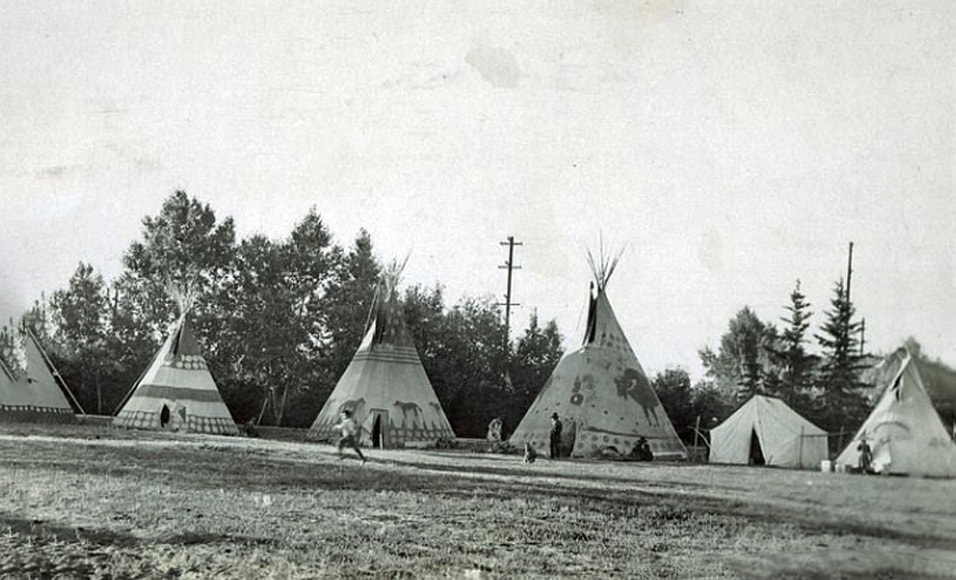

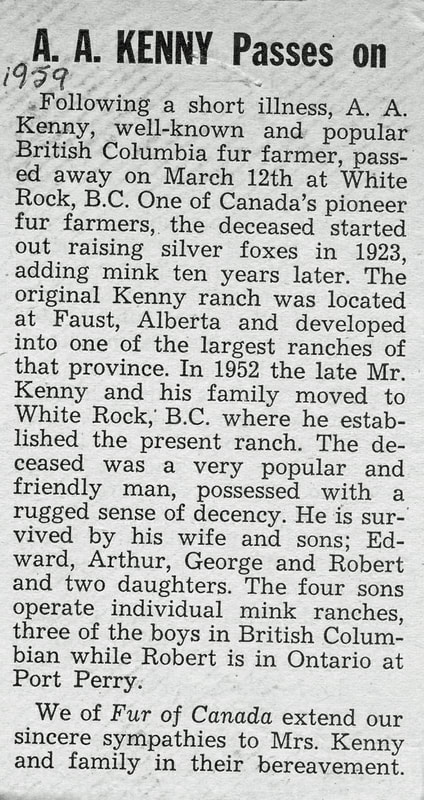

m) - ENTER: THE FUR INDUSTRY

In 1923, some of the local Indians came to Avery with a batch of fox cubs they had dug out of the hills. Avery traded a horse to them for the foxes, and set about building a place to keep them. An area sheltered by the hillside was fenced off by standing rough planks on end in a large square. A huge mound of soil was placed in the centre, providing a place for the foxes to dig their own lair. This provided warmth in winter, coolness in the hot summer, and a safe haven where the babies could be born the next spring.

Until the fox pen could be built, the foxes were kept in the loft above the barn. When the news circulated about the need, old horses were brought to Avery from all around the country to be used for fox feed. The meat was cut in strips and dried by hanging them over wire which was strung through the trees. This was done in early spring before there were flies around. The strips were soaked in a pail of water each day, and thrown to the foxes. That was all that was needed, besides fresh water. There were red, silver, and cross foxes in the line.

Until the fox pen could be built, the foxes were kept in the loft above the barn. When the news circulated about the need, old horses were brought to Avery from all around the country to be used for fox feed. The meat was cut in strips and dried by hanging them over wire which was strung through the trees. This was done in early spring before there were flies around. The strips were soaked in a pail of water each day, and thrown to the foxes. That was all that was needed, besides fresh water. There were red, silver, and cross foxes in the line.

n) - GOODBYE TO FARM AND FRIENDS

The fur industry in the Kenny family had begun. Avery bought a small number of mink in the early thirties. In 1936, the family gave up the farm and moved to Faust, a small town on Lesser Slave Lake. They had been through the depression with all the hard times and hard work. There was little to show for it. This may have been the way it seemed. However, Alice's heart was warmed by an act of love from the women at Elmworth. There was a parting gift - perhaps it was the Friendship Quilt, which she had in her possession and treasured. It had the ladies names embroidered on it. The accompanying page reads as follows:.

Elmworth, Alberta June 19, 1936

Dear Mrs. Kenny:

We, your friends and neighbours of Elmworth, take this opportunity of expressing our great sorrow and loss at the thought of your departure from our midst. Perhaps most of us here came to Elmworth by Kenny's Crossing, and found a welcome at the foot of the hill and were cheered to know we had a friendly neighbour in the land. Our husbands and neighbours, who spent many happy hours under your roof, gained the vision and courage necessary to establish a hope under trying circumstances.

While yours was the lot of enduring extreme hardships, it was also your privilege of making a comfortable, cheery, home for your family, and encouraging innumerable others in the years when there were very few women in the country. In the succeeding years we have always been sure of help for any worthy cause.

We regret also the loss of your family whom we feel are a credit to you. Indeed our community will be much poorer through the loss of yourself, Mr. Kenny, and the children. We shall brave the hills and ford the river-crossing no more except when necessary, when our hearts will be saddened at the memory of the many times we spent there in a visit, at church, or picnic.

We beg of you to accept this humble token of our love and esteem. May it serve to remind you of your friends here whose good wishes follow you to your new home."

The names of twenty-two women were enclosed, but no record as to who wrote the speech. You can be sure tears were shed at the event when the gift and speech was given. These ladies were parting with a fun-loving, hard-working friend. One whose life as a pioneer along-side her husband had been a shining example to them all.

There was also a farewell from the neighbours on the Rio Grande side of the river. This was held at the Black's home, with a gift of money from those friends who had so little money to spare. It was a heart rending time.

Elmworth, Alberta June 19, 1936

Dear Mrs. Kenny:

We, your friends and neighbours of Elmworth, take this opportunity of expressing our great sorrow and loss at the thought of your departure from our midst. Perhaps most of us here came to Elmworth by Kenny's Crossing, and found a welcome at the foot of the hill and were cheered to know we had a friendly neighbour in the land. Our husbands and neighbours, who spent many happy hours under your roof, gained the vision and courage necessary to establish a hope under trying circumstances.

While yours was the lot of enduring extreme hardships, it was also your privilege of making a comfortable, cheery, home for your family, and encouraging innumerable others in the years when there were very few women in the country. In the succeeding years we have always been sure of help for any worthy cause.

We regret also the loss of your family whom we feel are a credit to you. Indeed our community will be much poorer through the loss of yourself, Mr. Kenny, and the children. We shall brave the hills and ford the river-crossing no more except when necessary, when our hearts will be saddened at the memory of the many times we spent there in a visit, at church, or picnic.

We beg of you to accept this humble token of our love and esteem. May it serve to remind you of your friends here whose good wishes follow you to your new home."

The names of twenty-two women were enclosed, but no record as to who wrote the speech. You can be sure tears were shed at the event when the gift and speech was given. These ladies were parting with a fun-loving, hard-working friend. One whose life as a pioneer along-side her husband had been a shining example to them all.

There was also a farewell from the neighbours on the Rio Grande side of the river. This was held at the Black's home, with a gift of money from those friends who had so little money to spare. It was a heart rending time.

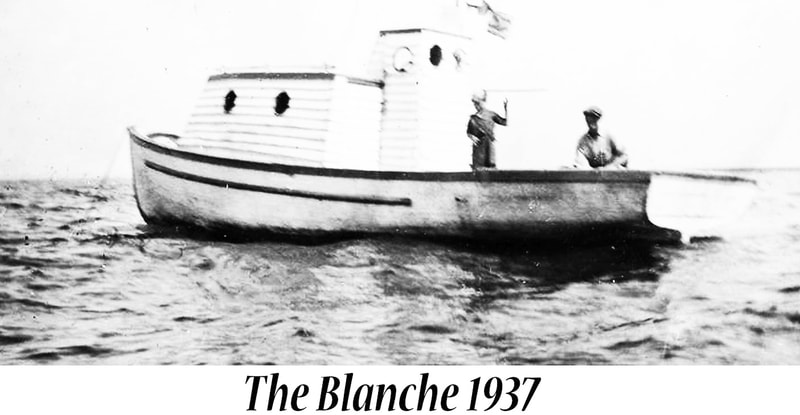

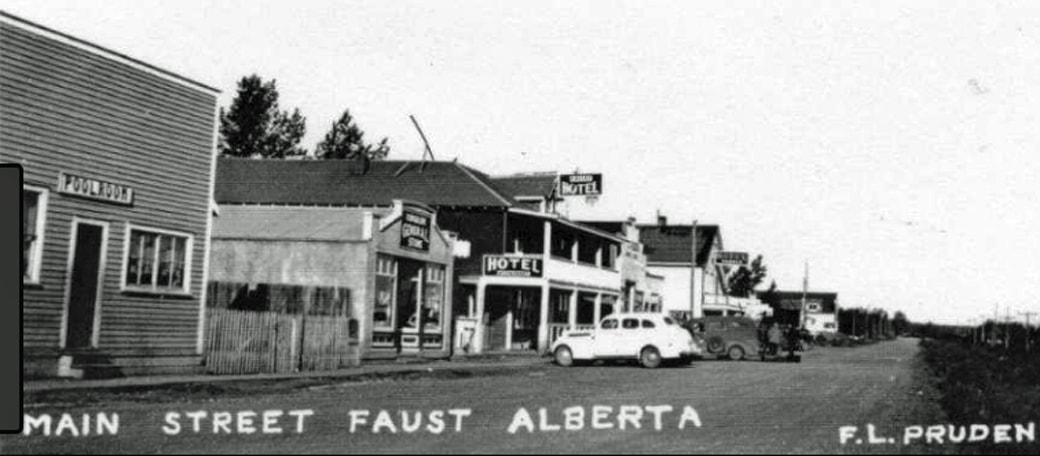

o) - LIFE AT FAUST

Hover over photos for caption, Click on images to enlarge:

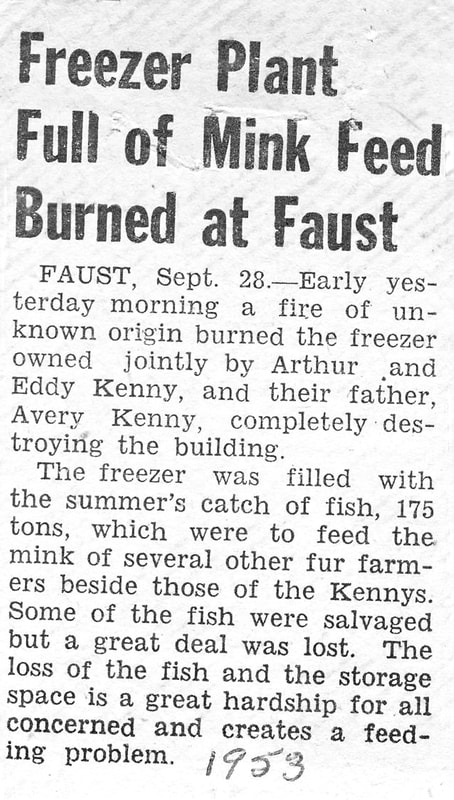

When the family moved to Faust, it was for the better financially. The regret was for the friends who were left behind. There was heartache for all of them over the little grave alone there under the trees. In the new location, Avery and Alice continued in the fur industry, and raised the family. Alice returned every summer to make the little grave neat by cutting the grass and planting flowers. The young man who leased the property for grazing land thoughtfully made a strong fence around the area to keep the cattle out. The family appreciated this kindness so much. Several years later, permission was granted by the government to have the grave moved to Victory Memorial Gardens, Surrey, B.C.

Shortly after arriving at Faust, Avery decided to give up the foxes. He began developing an excellent line of mink, for which he and the boys were to win many fine prizes in the years to come. The boys fished the lake for mink feed, and the girls attended school. George was only a little fellow when World War II came along. The war scattered the family for several years.

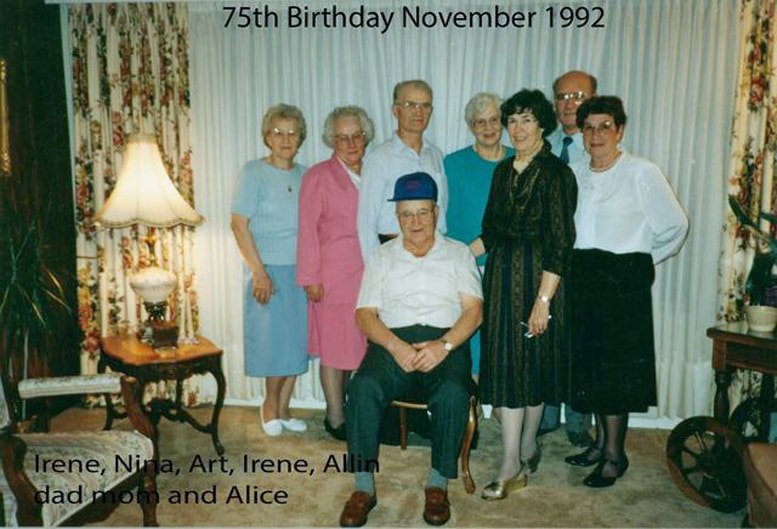

Robert joined the army soon after war broke out. He served in the Calgary Highlanders in England, France and Belgium. He was wounded in action, and spent some time in hospital. Upon his return home, he married his sweetheart, Norma Sinclair. They established a mink ranch, and a chicken ranch, and brought up their family, Sheila, Scott, Mark, and Ann in Port Perry, Ontario. Upon retirement, they moved to Comox, B.C.

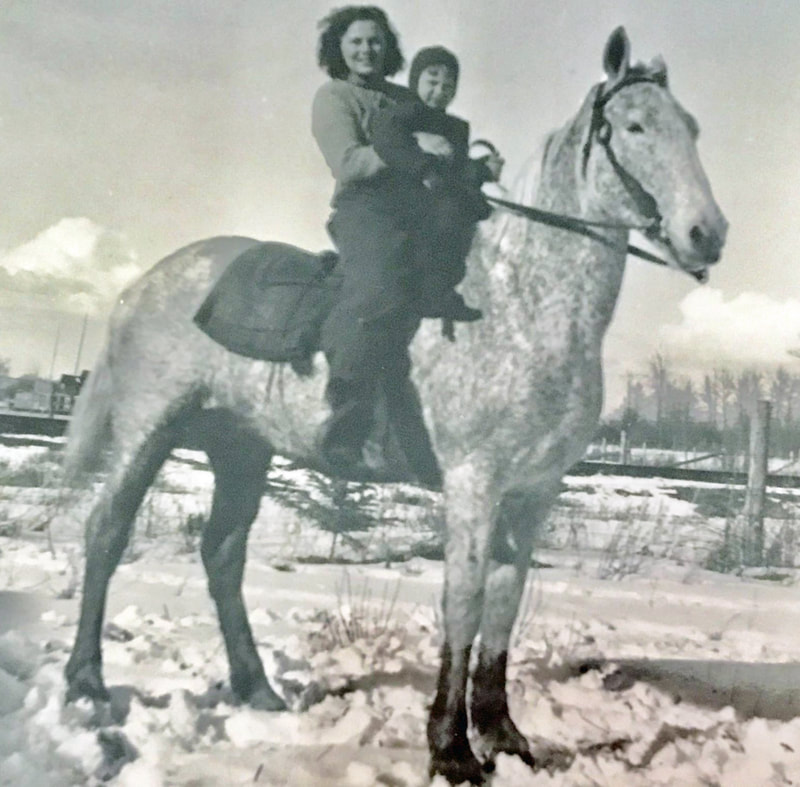

Eddy married Alice Treleaven, from Enilda, Alberta, in 1938 and settled in to a little house near mother and dad. He stayed on to help his dad with the mink ranch, and drove a road maintainer pulled by his horses for several years while at Faust. His love for horses continued after the move to White Rock in 1952, when he and Alice owned some very fine quarter horses, including a prize stallion named Guthrie Bob. They also had prize mink. Five children, Richard, Barbara, Marjory, and the twins, Doreen and Douglas, made up their family. Most of the children were excellent riders, winning prizes at horse shows and exhibitions. Upon giving up the mink raising, Eddy drove a school bus, and was loved by all the kids. He passed away with a heart attack in 1979.

While mourning the passing of my brother l was comforted by the Lord when He definitely said, "Eddy is with Me." Our fun-loving tender-hearted brother is gone, but he lives on in our dearest memories.

Arthur married Nina Sheldon, a young lady from Kinuso, Alberta, while in the Air Force during the war, shortly before going overseas. He served as an Airframe Mechanic in England. Upon his return home, he and Nina had four children, Ted, Linda, Roy and Karen. They set up mink ranching in Faust and moved to White Rock along with the rest of the Kenny's in 1952. There they settled in the Cloverdale area, and raised fine mink. When he gave up the mink ranching, Arthur worked on the B.C. Ferries for several years, and later as a gardener.

Marion joined the WRENS during the war, and was stationed in Ottawa and Halifax. There she met Jimmy Walker, who was with the Merchant Navy. After the war they were married at Faust and later returned there to establish a home and a mink ranch. They had a family of four fair haired boys, Dale, Randy, Gordon and Gary. They made the move to White Rock along with the rest of the Kenny's, and raised mink. When the wearing of mink went out of style, they stopped raising them, and Jimmy worked for Canada Customs. For a few years, Marion and Jimmy were separated. Jim later passed away. Marion worked for George and Sylvia on their mink ranch, and also for Irene and Alfred in their Ear Protection business. She is now retired and lives in White Rock.

George spent the greater part of his life raising mink, first helping his mother and dad, and then working the home ranch which he inherited. He married Sylvia Ready and they had a family of five girls, Georgia, Cory, Jillian, and the twins, Leslie and Lisa.

Shortly after arriving at Faust, Avery decided to give up the foxes. He began developing an excellent line of mink, for which he and the boys were to win many fine prizes in the years to come. The boys fished the lake for mink feed, and the girls attended school. George was only a little fellow when World War II came along. The war scattered the family for several years.

Robert joined the army soon after war broke out. He served in the Calgary Highlanders in England, France and Belgium. He was wounded in action, and spent some time in hospital. Upon his return home, he married his sweetheart, Norma Sinclair. They established a mink ranch, and a chicken ranch, and brought up their family, Sheila, Scott, Mark, and Ann in Port Perry, Ontario. Upon retirement, they moved to Comox, B.C.

Eddy married Alice Treleaven, from Enilda, Alberta, in 1938 and settled in to a little house near mother and dad. He stayed on to help his dad with the mink ranch, and drove a road maintainer pulled by his horses for several years while at Faust. His love for horses continued after the move to White Rock in 1952, when he and Alice owned some very fine quarter horses, including a prize stallion named Guthrie Bob. They also had prize mink. Five children, Richard, Barbara, Marjory, and the twins, Doreen and Douglas, made up their family. Most of the children were excellent riders, winning prizes at horse shows and exhibitions. Upon giving up the mink raising, Eddy drove a school bus, and was loved by all the kids. He passed away with a heart attack in 1979.

While mourning the passing of my brother l was comforted by the Lord when He definitely said, "Eddy is with Me." Our fun-loving tender-hearted brother is gone, but he lives on in our dearest memories.

Arthur married Nina Sheldon, a young lady from Kinuso, Alberta, while in the Air Force during the war, shortly before going overseas. He served as an Airframe Mechanic in England. Upon his return home, he and Nina had four children, Ted, Linda, Roy and Karen. They set up mink ranching in Faust and moved to White Rock along with the rest of the Kenny's in 1952. There they settled in the Cloverdale area, and raised fine mink. When he gave up the mink ranching, Arthur worked on the B.C. Ferries for several years, and later as a gardener.